Researchers in Australia have developed a 10-minute test that can detect the presence of cancer cells anywhere in the human body, according to a newly published study.

The test was developed after researchers from the University of Queensland found that cancer forms a unique DNA structure when placed in water.

The test works by identifying the presence of that structure, a discovery that could help detect cancer in humans far earlier than current methods, according to the paper published in journal Nature Communications.

“Discovering that cancerous DNA molecules formed entirely different 3D nanostructures from normal circulating DNA was a breakthrough that has enabled an entirely new approach to detect cancer non-invasively in any tissue type including blood,” Professor Matt Trau said in a statement.

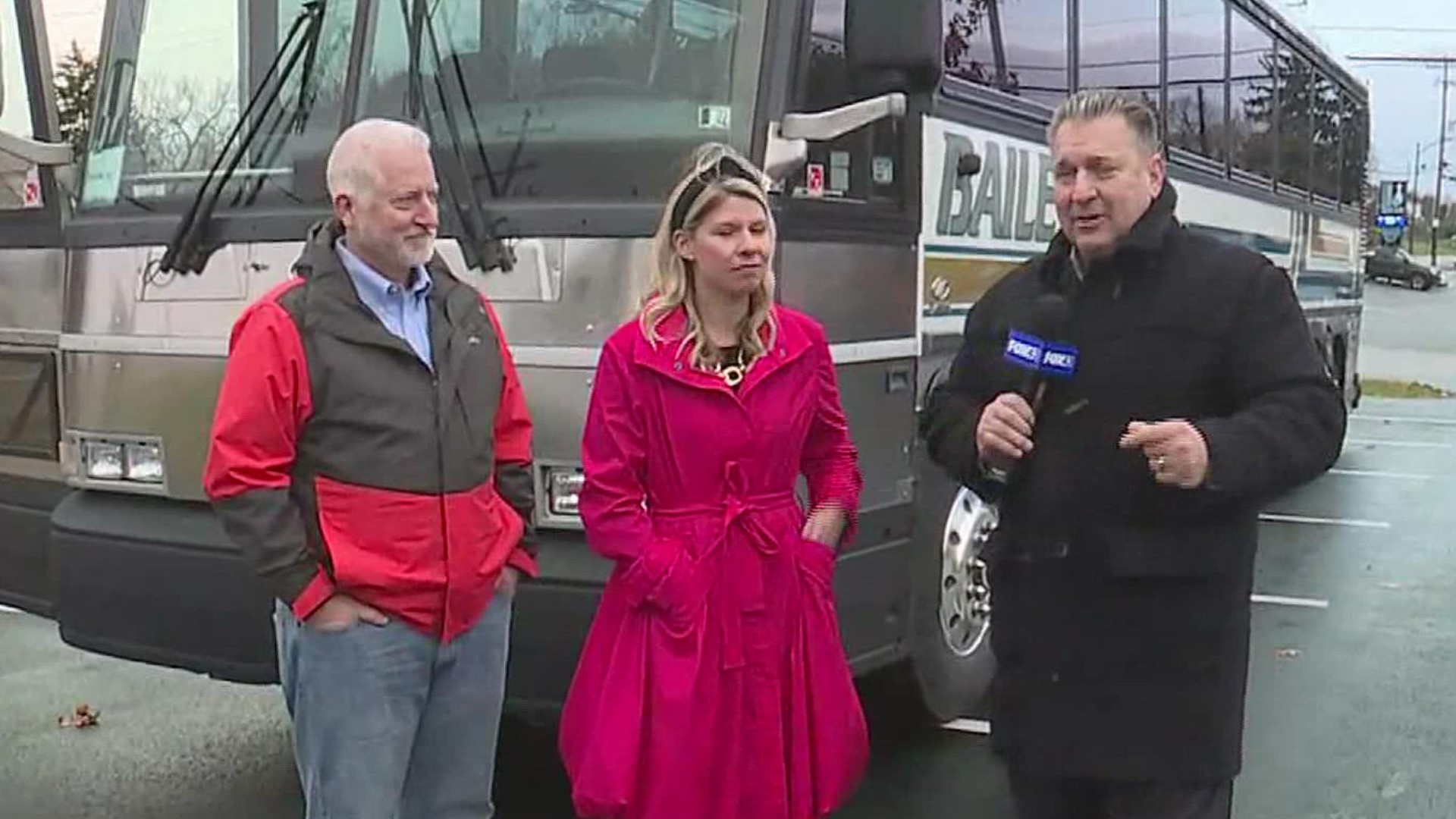

“This led to the creation of inexpensive and portable detection devices that could eventually be used as a diagnostic tool, possibly with a mobile phone,” he added.

Co-researcher Abu Sina said the findings represented a “significant discovery” that could be a “game changer” for cancer detection.

“Cancer is a complicated disease, [and currently] every type has a different testing and screening system. In most cases, there is no general test to test their status.

“Now, people only go [to get checked out] if they have symptoms. We want [cancer screening] to be part of a regular checkup.”

Scientists worldwide have been working on ways to identify cancer earlier, as early detection is known to increase the success rate of therapeutic treatment and surgery.

This year, researchers at Johns Hopkins University in the United States announced they’d developed a blood test, called CancerSEEK, that screens for eight common cancer types. That test identifies the presence of cancer proteins and gene mutations in blood samples. Much more research needs to be done before that test can be widely used, the US researchers added.

How it works

The 10-minute test developed in Australia is yet to be used on humans, and large clinical trials are needed before it can be used on prospective patients. But the signs are positive.

Tests on more than 200 tissue and blood samples detected cancerous cells with 90% accuracy, the researchers said.

It’s been used only to detect breast, prostate, bowel and lymphoma cancers, but they’re confident the results can be replicated with other types of the disease.

“Researchers have long been looking for a commonality among cancers to develop a diagnostic tool that could apply across all types,” wrote Trau and his research partners, Sina and Laura Carrascosa, in an article for academic news site The Conversation.

Cancer alters the DNA of healthy cells, particularly in the distribution of molecules known as methyl groups, and the test detects this altered patterning when placed in a solution such as water.

“Using … a high-resolution microscope, we saw that cancerous DNA fragments folded into three-dimensional structures in water. These were different to what we saw with normal tissue DNA in the water,” the article explains.

The test uses gold particles, which bind with cancer-affected DNA and “can affect molecular behavior in a way that causes visible color changes,” it added.

Carrascosa says that if proved, their method for detecting cancer could be a boon to providing detection and diagnosis in rural or underdeveloped areas. The technology for reading electrochemical signals is readily available, she says, and paired with a smartphone could be adapted to screen DNA affected by cancer.

“The advantage of this method, it is so simple — it’s almost equipment-free. You can do it with very low resources.

“There’s another possibility that it can be used to monitor for relapses. We haven’t tested that yet, but it is a potential.”

The next step for the team is to stage clinical studies into how early cancer can be detected,and whether the test can be used to gauge the effectiveness of treatment.

They’re also looking into the possibility of using different bodily fluids to detect different cancer types from early to the later stages of the disease.