PENNSYLVANIA, USA — Pennsylvania is home to an abundance of unique and diverse species spread across the state, and those include 23 that are recognized as endangered by the Commonwealth.

Among these animals facing extinction hides a solitary, shy bat that spends its days traveling throughout the Northeast and nights eating a variety of pesky insects: The northern long-eared bat.

These bats spend their summers traveling throughout the forest, typically by themselves or in small groups. They then travel up to 35 miles from these initial summer habitats to find a proper place to hibernate during the harsh winter months.

The northern long-eared bat is one of four bats recognized as endangered on a statewide level in Pennsylvania; however, their federal endangered ruling was recently extended.

"The northern long-eared bat was never an abundant species to begin with," Stephanie Stronsick, the executive director and founder of Pennsylvania Bat Rescue in Mertztown told FOX43. "Since the presence of white-nose syndrome in Pennsylvania, there's a 99% decline throughout the hibernation spots they are occupying."

Northern long-eared bats can be found in 37 states in the United States, as well as eight Canadian provinces, but many fear the species is flying too close to extinction.

WHITE-NOSE SYNDROME

Bats all throughout North America have been combating white-nose syndrome since it was first discovered in 2006. Sadly, northern long-eared bats are no exception.

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a disease that originates from the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd) and appears as a white, dusty growth that grows on the exposed skin of hibernating bats.

This disease has spread like wildfire among the bat population due to bats being typically sociable creatures, and congregating together can be extremely common.

"One of the most highly impacted species, the northern long-eared bat, tends to roost alone, or in small groups, but they share the same hibernation sites with other species, increasing their potential to become infected," stated Christina Kocer, the Northeast Regional Contact for the White-Nose Syndrome Response Team.

"Once fungal spores have been introduced into a site, they can remain in the habitat for a long time, re-infecting [bats] as they come in contact with the surfaces of the habitat year after year," Kocer explained.

The non-native Pd fungus thrives in cold environments, which gives bats who hibernate in caves or mines all the more opportunity to get exposed.

Upon coming into contact with the spores, the fungus will begin to grow on the exposed areas of the hibernating bat's skin. The growth rate progresses at a fast pace since a hibernating bat's immune system will be drastically reduced.

The bat will begin to wake up from their hibernation as the infection progresses and causes more irritation. The constant waking up forces necessary energy and fat reserves to begin depleting, which can be detrimental to surviving the winter months without.

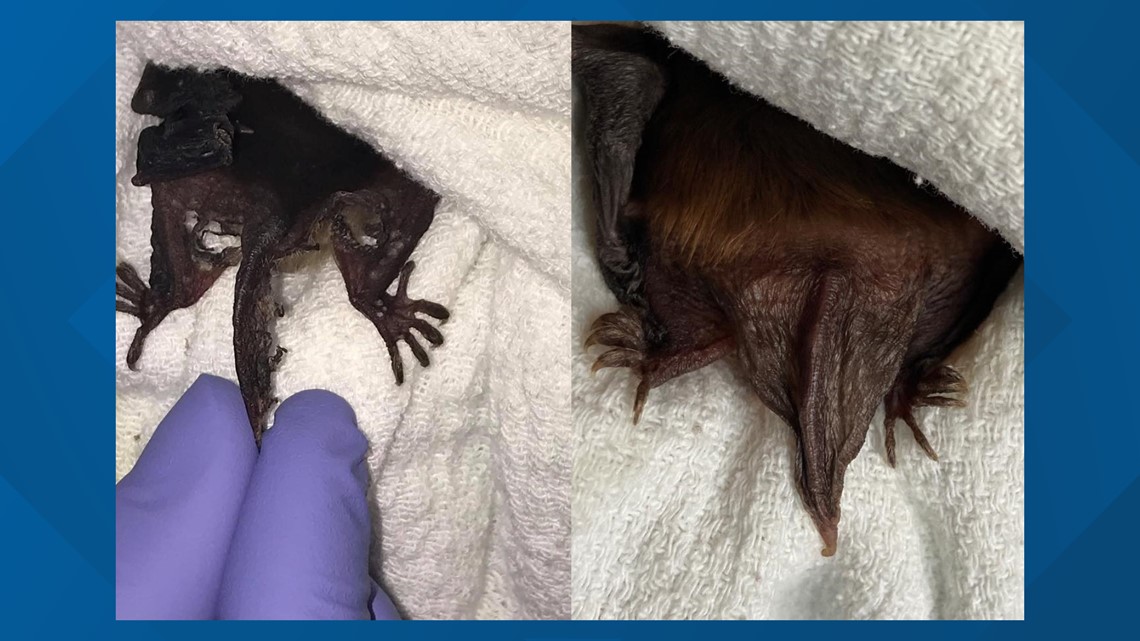

The invasive infection will target the bats' vulnerable wing membranes the most, resulting in a plethora of physiological changes - such as weight loss, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and death.

Once the infected bats' hunger increases, they will begin to venture outside of their hibernation site to find food. However, due to the difference in winter temperature, the bat will find no sight of their usual prey, and slowly starve.

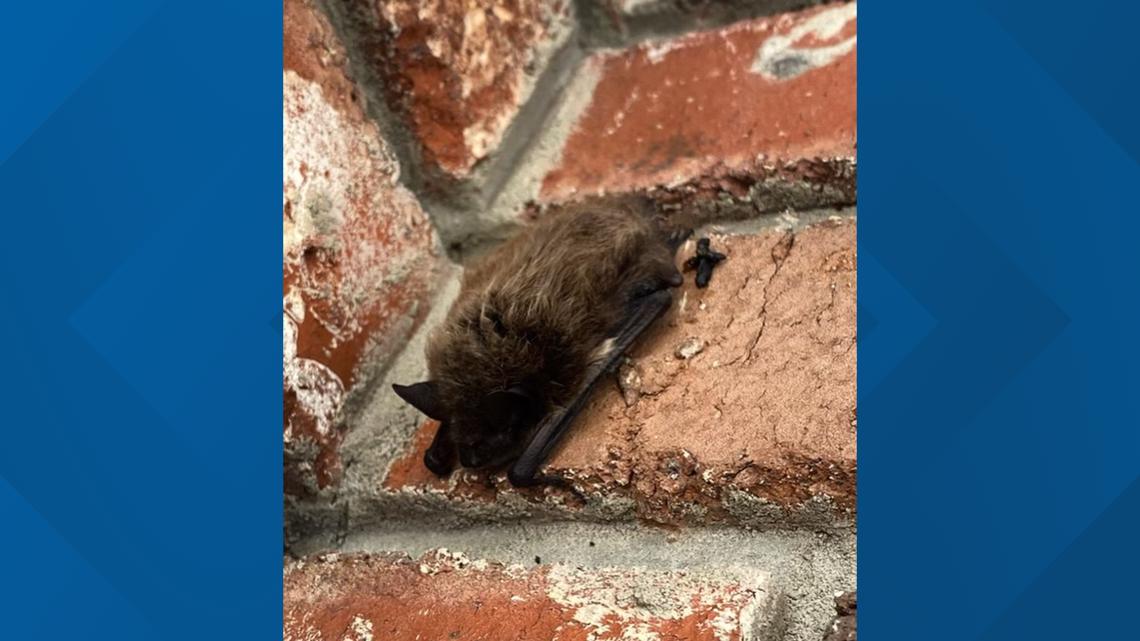

When asked if there have been any noticeable trends witnessed in the northern long-eared species, Stronsick stated, "We have noticed more increasing situations where they are roosting low on the sides of buildings. While they are migrating they are running out of energy and hydration, which causes them to pick a place to roost which [may] not always be the best."

And if you see one of these bats hanging low on the side of a local business? "We tell people just don't touch them and give us a call right away," Stronsick advised. "It's important to notify us first because we have the proper permits to care for them."

CONSERVATION EFFORTS

One of the biggest struggles in the bat community has been how to properly tackle the spread of WNS. Scientists haven't found a cure and are currently testing an assortment of different methods.

"It is important to have multiple tools in the toolbox when addressing WNS as every site, species and situation is different," stated Kocer.

This can be seen in the difference in treatment implementation for a bat if they need probiotics or vaccines, or even if they need treatment to be applied in varying sites. Kocer acknowledged that these questions are answered, it's easier to determine the most effective, and specific, treatment plan.

The main conservation efforts currently include disease management, such as national decontamination protocols, and hibernacula protection.

Decontamination has been introduced into many caving excursions, due to the Pd spores' ability to cling to anything. Spores can survive for an extended period of time, so protocols were established to minimize the spread by humans.

If you really can't miss your next cave adventure, Kocer advises, "Follow decontamination guidelines to clean the disease-causing fungus off clothing and gear and don't move gear from sites with the fungus to sites without it."

Minimizing disturbances is the best way to protect hibernating bats, which is why the Pa. Game Commission strongly recommends against recreational caving from Oct. 1 through April 30.

WAYS TO HELP

Some people have experienced a bat encounter either inside their house or somewhere nearby, but it's more important now than ever to protect bats who fly into the wrong place at the wrong time.

"During the summer months, if there’s a colony in [your] attic, they will migrate in the fall, and then you can take appropriate measures to seal up that home," Stronsick instructed, "During the summer, evictions aren't allowed in Pa., so bats are protected because [they] are a slow-reproducing mammal."

Once patching up your home after the colony leaves, it's recommended to construct a few bat houses, so that way the bats in your community have a safe place to roost without invading homes.

It's also helpful to the bats around you to begin your own native garden, which attracts the specific insects that bats eat. Some specific plants include garden phlox, wild hydrangeas, common evening primrose, and white trillium - all attract moths, which is one of the easiest night-flying insects to attract.

The special garden should be placed away from bright lights and loud noises so that during the night your new fanged friends will feel comfortable enough to stop by and dine.

Bats aren't always perceived in the best light by the general public and that has a tendency to make it more difficult for some people to emphasize.

"In my experience, once someone learns that a tiny bat can live for 10+ years, or that they only have one pup per year, or that they are the primary predator of Kocer expressed.

Alongside constructing bat houses for your community, starting bat-friendly gardens, and learning to cohabitate, Stronsick also recommends helping out your local bat rehabilitation center.

"[Pa. Bat Rescue is] one of the larger bat rehabilitation centers in the Northeast. We take in over 300 bats a year, and our goal is to release them," said Stronsick. "Of course, following any wildlife or bat rehab center and supporting them in anything they need, like supplies or monetary donations [helps them out]."

While it can be frustrating to think about the lack of a clear cure in regard to WNS, officials believe that the newfound public attention will help bats return to the skies in larger numbers with every passing year.