COLUMBUS, Ohio — A groundbreaking treatment for the most common form of muscular dystrophy has been approved by the FDA.

The gene therapy provides new hope for the 20,000 children globally diagnosed with this life-threatening disease each year—and it's improved the lives of the first children to receive it in clinical trials.

Easton Reed and Connor Stoll live hundreds of miles apart, but they share many of the same challenges.

"He had a hard time keeping up in sports and couldn't run quite as fast as the other kids," Stephen Stoll, Connor's dad, said.

"It wasn't uncommon for him to have bumps and bruises on his head because he fell a lot," Alan Reed, Easton's dad, said.

Both boys have Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, a genetic disease that leaves families with few options and little hope.

"When we did the research, it was so very scary to think what Easton's future might look like," Cassie Reed, Easton's mom, said.

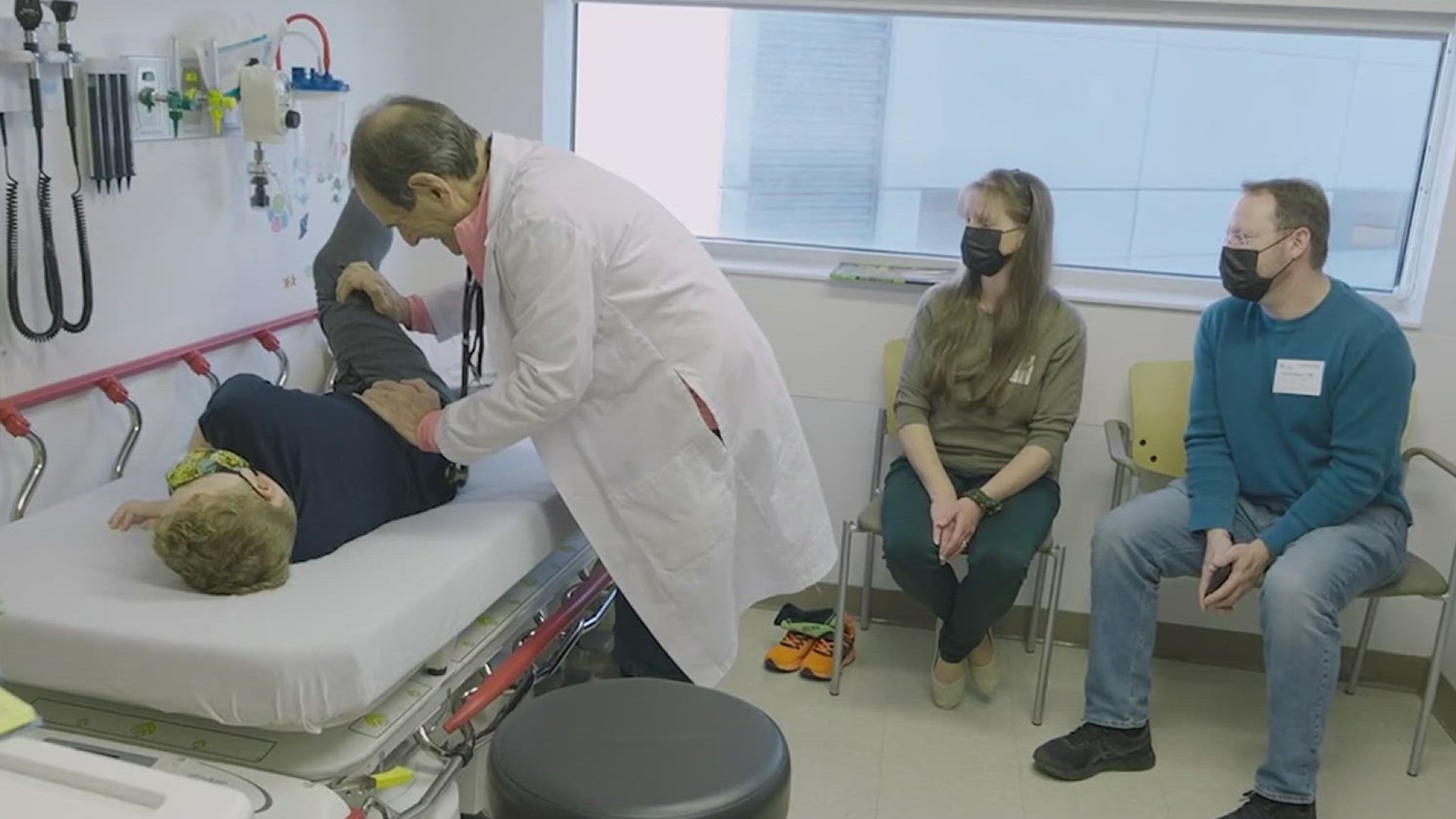

Doctor Jerry Mendell has dedicated his career to working with his team at Nationwide Children's Hospital to better understand and treat this progressive neuromuscular disease.

"Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a severe, life-threatening and devastating disease. They lose ambulation in teenage years then respiratory and cardiac involvement and early death," Dr. Mendell said.

Connor and Easton were among the first participants in a clinical gene therapy trial to correct the function of the gene that causes DMD. Five years after receiving the single gene therapy infusion, both boys have maintained their mobility—something that's rare in kids with DMD by this age.

"We started noticing that stairs were a little bit easier for him to climb," Kathryn Edison, Connor's mom, said.

And for the first time, Easton and Connor's families are seeing new possibilities.

"This therapy gave Easton his childhood and let him be a little boy," Cassie Reed said.

"We were able to visualize his future and what he could become and everything that he could be great at," Edison said.

Now, thousands of others who feared their children would slowly succumb to the disease have hope for a longer, healthier future.

"But we tell him all the time he's done remarkable things and he's helping boys everywhere," Cassie Reed said.

As doctors learn more about the long-term effects and benefits of the gene therapy, supplemental treatments for kids like Connor and Easton are being developed further to slow disease progression and improve mobility.