PENNSYLVANIA, USA — Black people in America get sicker and die earlier than other ethnic groups.

According to the Robert Wood Johnson foundation, a public health philatrophy, Black Americans live, on average, until they are 75 years old. It is the lowest total of any ethnic group, and 3.7 years fewer than white people. In Pennsylvania, the gap is even greater; Black men and women die, on average, at 73.2 years of age in the Keystone State, which is more than five and a half years less than white people.

When you consider the damage caused by COVID-19, Black people are dying at 1.4 times the rate of white people, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project.

Before you address the issues plaguing African Americans today, you have to acknowledge a problem exists, says Chastity Frederick, a registered nurse with the York City Bureau of Health. Frederick, who is white, says more than 50% of the people she works with are not white, and that has changed how her job functions on a daily basis.

"As a person who is not a person of color, one of the first things that I've needed to do, and continue to do, is to listen, and to learn," Frederick said. "It’s the three Ls: listen, learn, and lean in. I start to understand the experiences of people of color have had, and still have."

Frederick says having a cultural and historic awareness helps start the process of eliminating personal biases. Once that happens, she and her colleagues at the York Bureau of Health are able to have deeper conversations with families about making sure they are getting the health care they need.

"I empower people to advocate for themselves, so they can advocate for their community and families," Frederick said. "That’s really important that people understand that they have a right to advocate for themselves and advocate for their care. A lot of people say they don’t understand the help when they go, and that’s OK. But it’s also OK to ask questions."

Communication gaps have existed between ethnicities and racial groups throughout time. However, when those gaps result in a lack of quality health care, people potentially die. Addressing those gaps is the main focus of Dr. Jaya Aysola, the executive director of Penn Medicine's Center for Health Equity Advancement in Philadelphia.

Dr. Aysola's team has done numerous studies over the years, focusing on implicit biases which exist in doctors and other health care professionals. A recent study suggested ways to fix race-based discrepencies in health care start within their own house.

"We looked at the providers and how our students are being trained, in terms of the way race is used, and the way we talk about race, and how we define race-based differences in health outcomes," Dr. Aysola said, adding similar studies occurred at other major medical universities, like Brown, Yale, and Harvard. "If we address some of that as a medical community, then we can move the needle.

"What you find is, whether it's the healthcare system or the criminal justice system, all of these social systems are laden with structural bias and then individual unconscious bias that sets the stage for this perfect storm of factors that result in certain communities being burdened with poor health outcomes."

Another study recently done by Dr. Aysola's team found Black babies are twice as likely to be born preterm than white babies. According to Chastity Frederick's statistics in the York City Bureau of Health, one in every nearly six Black babies are born early.

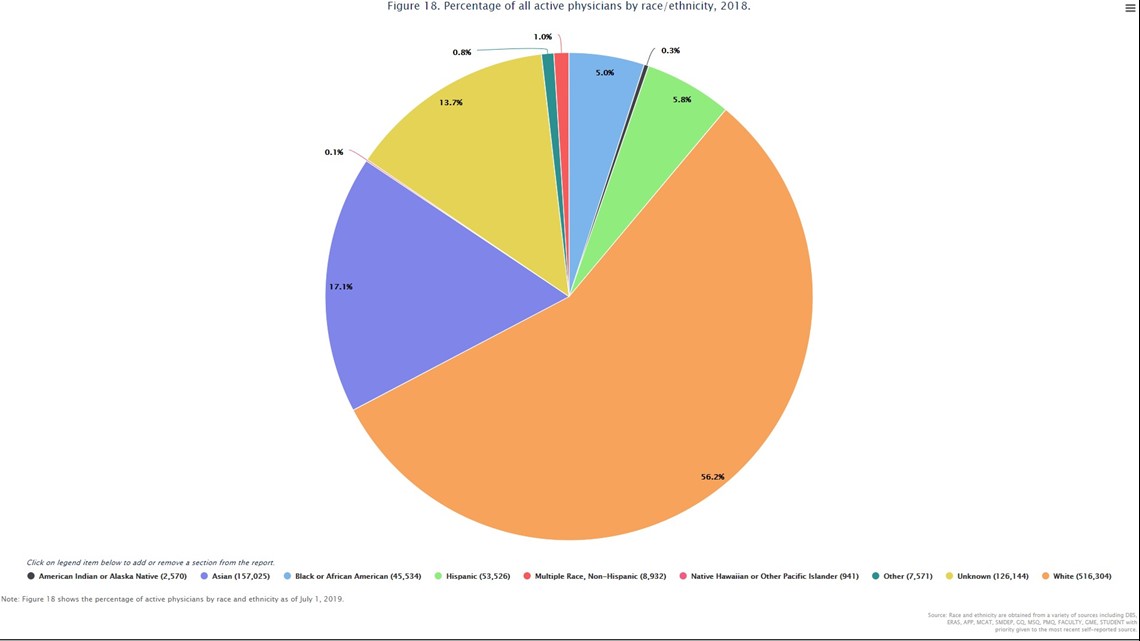

According to the Association of Medical Colleges, only 5% of active physicians, as of 2018, were Black. The same study showd 56% of all practicing doctors were white.

The call to improve health care for minority communities can also be found in state government. Last summer, Pittsburgh-based State Representative Jake Wheatley (D-Allegheny) proposed a bill which would have addressed health inequities in people of color. It would have created a racial equity task force within the Pennsylvania Department of Health to address systemic racism in all Pennsylvania communities.

"People of color live all across the Commonwealth and they're not just an urban settings," said House Democratic Leader Joanna McClinton (D-Philadelphia). They are in rural communities as well, so we don't want to leave any of our Pennsylvanians at risk."

McClinton says she expects Wheatley's bill to be introduced this legislative session in the near future. She admits it is difficult for House Democrats to have their bills heard in by a Republican-controlled legislature, and hopes to find a Republican to support it in a bipartisan fashion.

Among the issues McClinton wants the bill to address include helping Black men and women in cities get easier access to the COVID-19 vaccine, while also addressing an issue facing more rural communities, where there are no hospitals within dozens, if not hundreds of miles.

"We have to be able to bridge the gap, because we’re never going to come out of this pandemic if there’s not health care access locally," McClinton said. "We need to make sure neighbors all throughout Pennsylvania are treated equitably and fairly and that there aren’t any folks that can't take care of themselves because they can’t afford it, or if they don’t have a primary care provider."