Much like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, or the morning of September 11, 2001, most Americans remember where they were when they heard the news of the Challenger disaster.

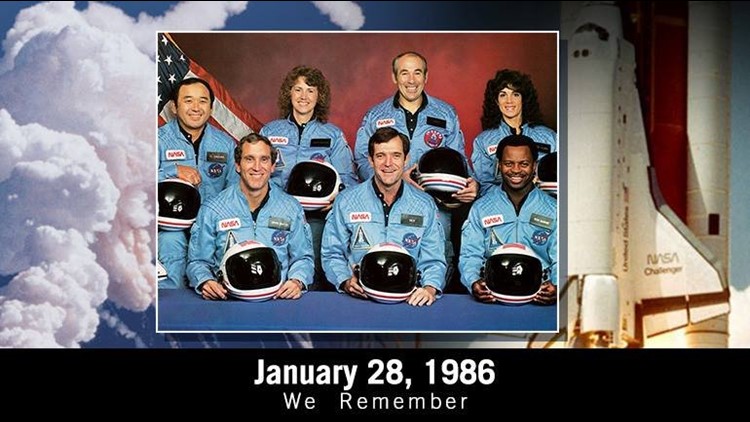

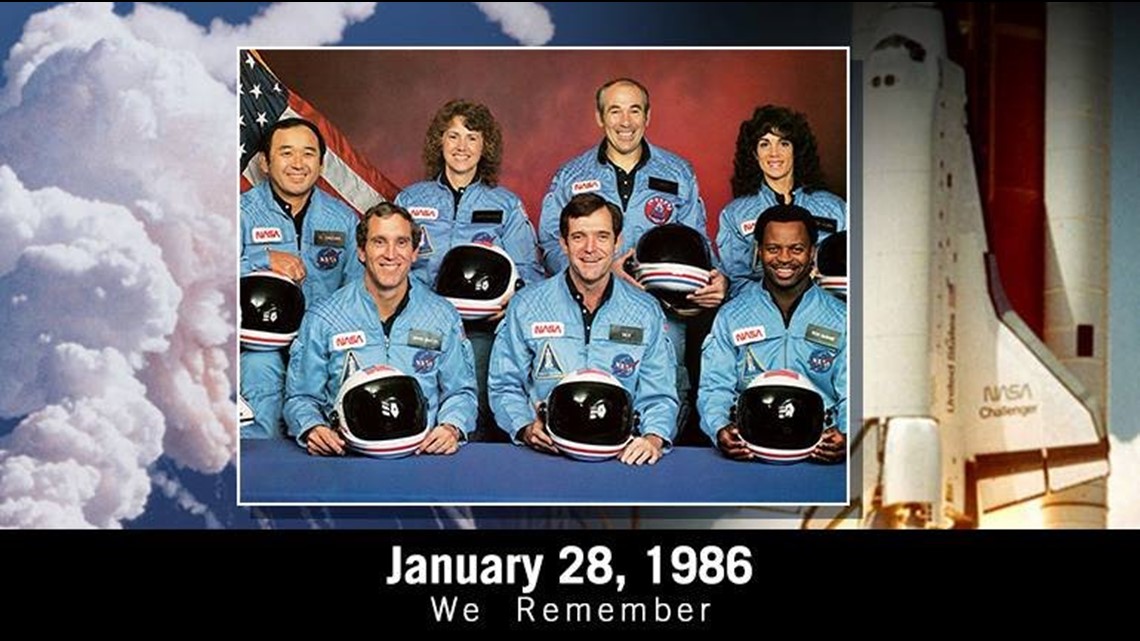

It was NASA’s first in-flight tragedy. Challenger launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 28, 1986. Shortly after liftoff, the space shuttle’s external fuel tank collapsed, causing what looked like an explosion, and the shuttle broke apart and fell approximately 46,000 feet to the Atlantic Ocean, killing the seven crew members aboard.

The tragedy unfolded on live TV — and the audience watching was particularly young.

Christa McAuliffe, a high-school teacher from New Hampshire, was one of the seven; she was set to be the first civilian and teacher in space. NASA had arranged a satellite broadcast of the full mission for students to watch the historic moment in schools across the nation.

Clarence Searles was a second-grader at Challenger Elementary School in New Jersey that year. He loved planes and wanted to be an astronaut, and he remembers sitting with the other children in his class to watch the launch. “Pretty much everything had stopped” when the Challenger exploded, he remembers.

“We were all trying to make sense of it,” Kathryn Stuart says. Her second-grade class at Blankner Elementary in Orlando, Florida, watched the launch from the school playground. “They took us off the playground as quickly as they could, and we went back to class.”

That night, President Ronald Reagan addressed the country, speaking directly to the nation’s children: “I know it is hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It’s all part of the process of exploration and discovery.”

It was later determined that cold weather, combined with a design flaw, led to the accident. A seal on one of the solid rocket boosters was not working properly. The disaster grounded NASA’s space shuttle program for nearly three years.

“But look at how we flew after,” says Robert Cabana, former NASA astronaut and director of the Kennedy Space Center. Cabana says scientists made over 100 changes to the shuttle to make it safer and more reliable. NASA also changed its culture, he says, after learning engineers had raised concerns about the Challenger’s launch before it happened.

“We could have prevented that from happening,” Cabana says. “That’s why it’s really important that we always, always ask questions and listen.”

Since 1986, NASA has landed multiple rovers on Mars and discovered flowing water on the Red Planet. It’s completed the International Space Station, where astronauts have lived for 15 years. It’s sent New Horizons to Pluto to take photos of the dwarf planet.

As Reagan said in that same speech, “The future doesn’t belong to the faint-hearted; it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we’ll continue to follow them.”

To honor the crew, their families and friends came together to establish the Challenger Center. The mission was much like the Challenger’s: to spread STEM education. Today, more than 40 education centers around the country help millions of kids learn about science and space; there they are encouraged to reach for the stars.

“That’s really the legacy I think of Challenger — that mission, that focus on outreach and education,” says Capt. Kenneth S. Reightler, a former astronaut. “I think (the Challenger crew members) would be very, very proud.”