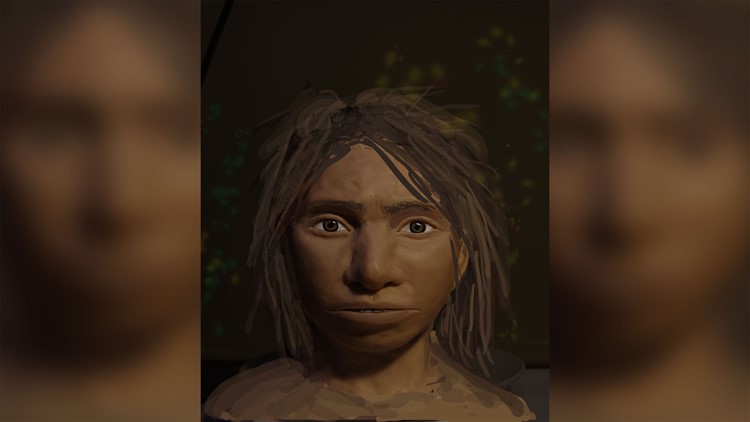

We know that mysterious ancient humans called Denisovans once lived alongside Neanderthals, thanks to a few bones and teeth recovered from a cave in Siberia. Now, for the first time, researchers have shared what they might have looked like.

The previously recovered bone fragments include a pinky bone, teeth and a jawbone. Denisovans also left a genetic legacy that lives on today in the DNA of some Asians, Australians and Melanesians. A Denisovan genome was sequenced in 2012 and compared with that of modern humans, revealing the trait.

Denisovans not only interbred with Neanderthals, but with archaic Eurasian humans as well. Because their DNA lives on in some humans today, researchers have reason to believe that they once lived all throughout Asia. Yet, the fossil record is incredibly sparse.

Scientists may have been able to sequence their genome, but this small fossil record made it difficult to piece together their appearance — until now.

In order to piece this puzzle together, researchers had to go a different route than normal reconstruction: DNA methylation data.

This process relies on extracting information from gene activity patterns, rather than DNA sequences. These patterns are chemical modifications that don’t change the actual DNA sequence.

From these patterns, the researchers were able to predict Denisovan features. They began by comparing patterns between different human ancestor groups to find areas where they differed. They further analyzed the differences to determine how those might influence anatomical features. The researchers used current research on what we’ve learned about the different ways genes function to match those differences.

The study published Thursday in the journal Cell Press.

“We provide the first reconstruction of the skeletal anatomy of Denisovans,” said Liran Carmel, study author at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals, but in some traits, they resembled us, and in others they were unique.”

The researchers tested their method on Neanderthals and chimpanzees since their anatomies are both understood. Their method was 85% accurate in predicting how their traits differed and why, resulting in reconstruction.

“By doing so, we can get a prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change — for example, a longer or shorter femur,” said David Gokhman, study author and postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University.

When they applied this method to Denisovans, they found that 56 features were different from Neanderthals and modern humans. And 34 of those were in the skull alone, including a longer dental arch and a wider skull.

But they shared Neanderthal traits like wide pelvises and elongated, protruding faces.

While the research was being reviewed for publication, another study was released describing a Denisovan jawbone — which coincidentally, matched up with this study’s prediction.

The finger bone recovered in the cave represents the tip of the pinky finger from the right hand of a young female Denisovan, who was around 13.5 years old when she died 50,000 years ago. She’s known as Denisova 3. And the reconstruction is that of a young female Denisovan.

Going forward, the researchers believe that their DNA methylation method can even help reconstruct features that can’t be inferred just from studying fossils.

“Studying Denisovan anatomy can teach us about human adaptation, evolutionary constraints, development, gene-environment interactions, and disease dynamics,” Carmel said. “At a more general level, this work is a step towards being able to infer an individual’s anatomy based on their DNA.”