CARLISLE, Pa. — Several efforts are underway to honor the dead at a long-neglected African-American cemetery in Carlisle.

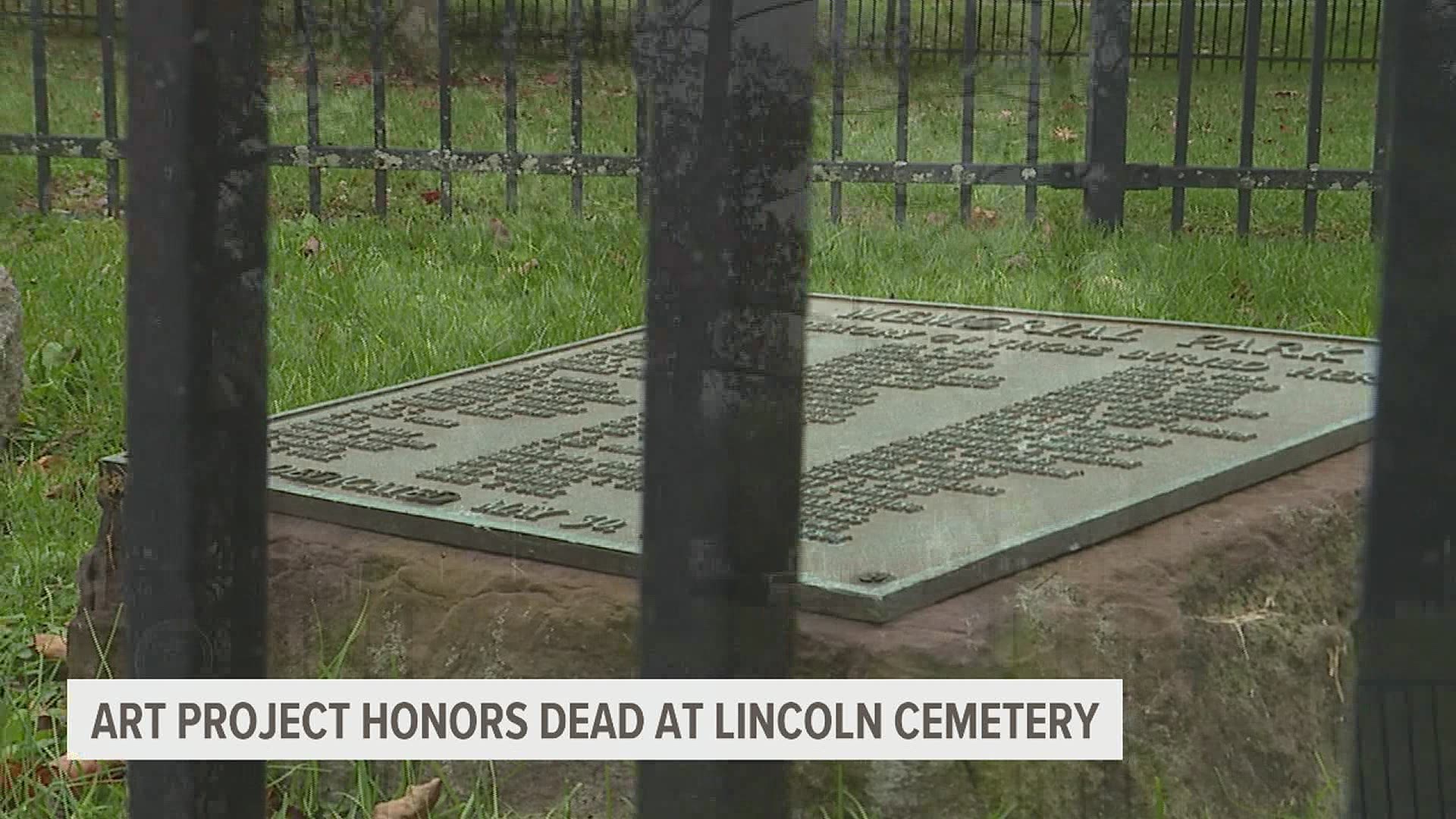

The current Memorial Park has a long-buried past as a cemetery, according to information from the Cumberland County Historical Society.

According to oral tradition, the Penn family deeded the land to the Black people of Carlisle when the town was laid out. Historians know for certain, however, that at least 400 people were buried there between 1804 and 1905, during which time its name changed from the African Cemetery of Carlisle to Lincoln Cemetery.

“We have people that have been enslaved, we have freedom seekers, over 50 Civil War veterans,” said Cara Curtis, the Historical Society’s archives and library director.

In 1972 Carlisle Borough removed all but one tombstone in order to build a park, which was completed in 1974.

The one tombstone left belonged to Samuel A. Jordan (1844-1903), an employee at the Carlisle Indian School.

One of Jordan’s descendants, Fleta Jordan, had fought to preserve his gravestone when the borough converted the cemetery into a park.

“The idea that it was a cemetery and it didn’t mean anything to the white population, just to remove the stones for no other reason than just to have a park, no consideration at all for the bodies that were interred in that cemetery,” said Wanda Hunter, a granddaughter of Fleta Jordan who lives in Carlisle.

The other gravestones were moved to a borough storage building, but were subsequently lost.

“That park in particular has a lot of different memories for me, some that aren’t so wonderful, but all kind of encompass who you are,” said Tawanda Stallworth, Wanda Hunter’s daughter and Fleta Jordan’s great-granddaughter.

About 50 years after the cemetery became Memorial Park, the community is reconsidering the event.

Carlisle Borough Council released a statement Monday apologizing for its role in removing the gravestones. The Sentinel reports the statement read in part:

“Carlisle Borough Council apologizes for any and all past participation in the sanctioning of segregation and systemic discrimination of African-Americans, particularly in relation to the events that led to the removal of all gravestones, except for one, in the Lincoln Cemetery in 1972.”

Community organizations have been working to improve and beautify the park in recent years.

The Army War College Class of 2019 donated an archway to the park inscribed with “Lincoln Cemetery.”

In early 2020 the Historical Society received a $2,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Council of the Arts to complete a project at the cemetery.

For the project the Historical Society partnered with local business Create-A-Palooza, which offers pottery painting and other art activities.

“We live here and so we want everyone here to enjoy living here and feel comfortable here. When we hear a story where cemetery headstones are removed and memories are lost and all that changed, that's troubling,” said Jim Griffith, who owns Create-A-Palooza with his wife Karen.

Initially the Griffiths thought they would donate ceramics and supplies to allow community members to paint tiles for a mosaic at the park. However the pandemic made ceramic-painting events impossible, so they decided to paint a mural with input from the descendants of those buried in the cemetery.

“All this is guided by the descendants and we still look at this like, how can we help you make this happen?” Griffith said.

The mural is inspired by a flag used by the U.S. Colored Troops during the American Civil War, Griffith said. The flag was an American flag with important dates or information written in gold inside the red stripes. In the Lincoln Cemetery mural, the red stripes are inscribed with the names of the Civil War veterans buried there.

The flag mural is surrounded by more painting that includes the last name of each family buried in the cemetery. That section is painted in red, black and green in honor of the Pan-African flag, created in 1920 to represent people of the African Diaspora and to symbolize black liberation in the United States.

Descendants will be invited to paint over the white name of their ancestor in yellow to signify how many people have ties to the cemetery.

Stallworth said she appreciated the art project, as well as the Borough Council apology, but felt more action was needed.

“Reactionary measures aren’t really the [right] move,” she said. “That’s not how progress is made and how substantive racial reconciliation happens.”

The Historical Society hopes to eventually install a more permanent monument in the park, as well as other improvements.