HARRISBURG, Pa. — The U.S. Postal Service’s motto states “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night” can delay the mail.

Sundays, however, were an impediment for one Lancaster County postal worker, whose religious discrimination lawsuit was heard by the Supreme Court on April 18.

When the Postal Service began delivering Sunday packages for Amazon in 2013, mail carrier Gerald Groff said his evangelical Christian faith prevented him from working on the Sabbath.

Groff was initially allowed to work a different shift instead of Sundays. The rural Quarryville and Holtwood post offices where he worked, though, struggled to find substitutes to work the unpopular shift. One carrier transferred and another resigned as a result of having to pick up the extra work, according to Groff’s supervisor.

By 2018, Groff had missed 24 Sunday shifts and faced two suspensions.

He resigned in 2019 and sued for religious discrimination.

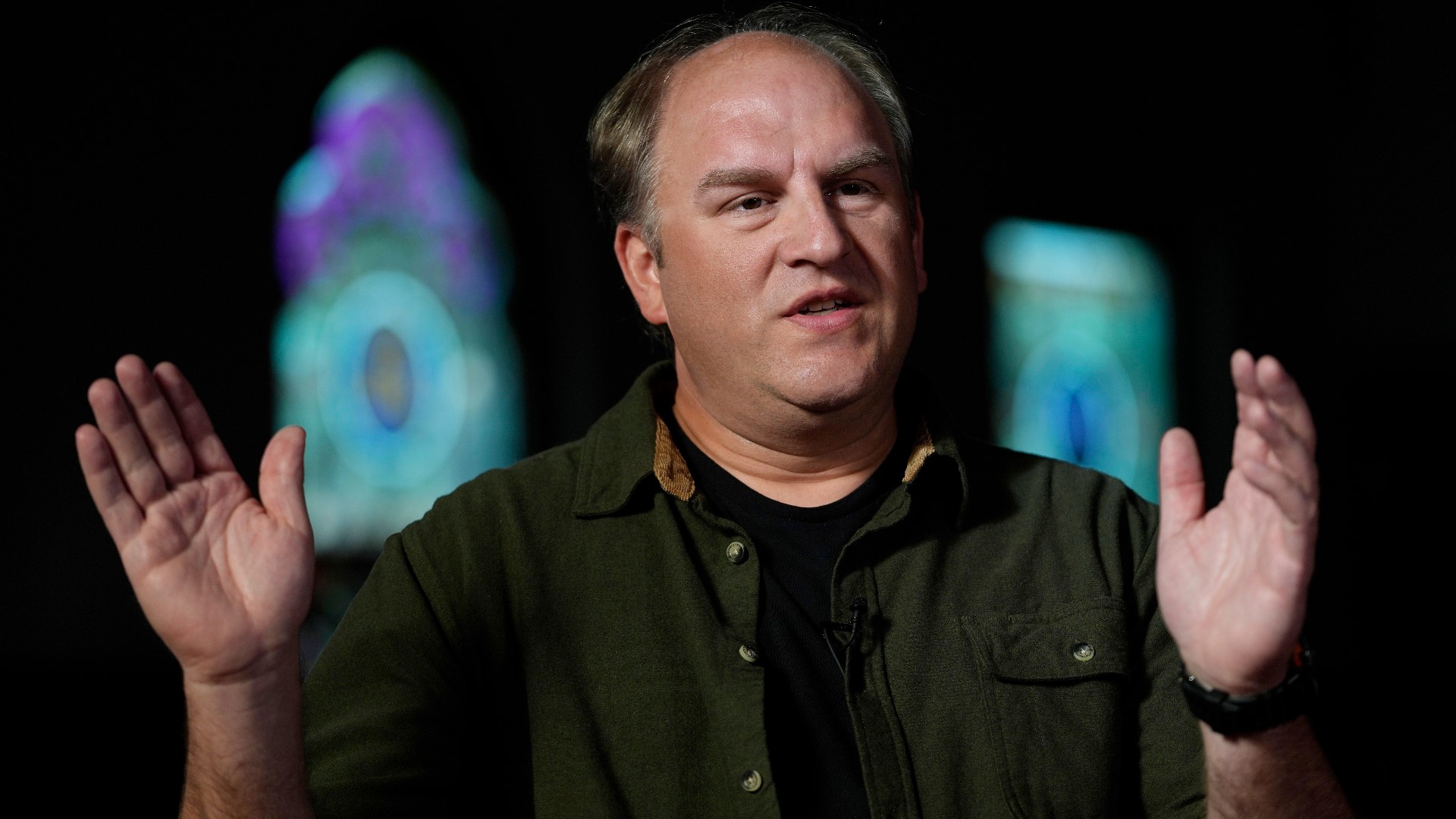

“No employee should have to make the decision that Gerald made, which was to choose between his career and his faith,” said Jeremy Dys, senior counsel of First Liberty Institute, one of the groups representing Groff.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination based on religion and since 1972 also requires employers to make reasonable accommodations for employees' religious beliefs or practices.

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday centering around “undue hardship,” the current standard for religious accommodation. The standard has been in place since a 1977 Supreme Court ruling.

“The U.S. Supreme Court interpreted ‘undue hardship’ to mean that no accommodation had to be provided if providing that accommodation would impose anything more than a trivial, de minimus, burden,” said Michael Dimino, professor of law at Widener University Commonwealth Law School.

The goal of Groff’s lawyers is to change that definition so that employers would have to allow more religious accommodations, such as not working on the Sabbath.

“The courts have watered down the standard that protects religious liberty in the workplace, for religious employees especially, for the last 40 or so years now. It’s time to restore religious liberty to its rightful place in the workplace,” said Dys.

The Department of Justice argued too much accommodation would hurt businesses, inconvenience other workers and upend established case law.

“Our concern with that is if the court were to announce a new standard, I think it would come with all the costs of destabilizing this area of the law,” said U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar. “Or potentially call into question all the established areas of law that have developed that we think have drawn the right lines here.”

The court’s ruling could have wide implications on how far employers must go to accommodate religious practices.

At least four members of the Supreme Court's 6-3 conservative majority have signaled they would support changing the religious accommodation standard to favor religious interests.

A ruling is expected by late June or early July.