CUMBERLAND COUNTY, Pa. — A home near Carlisle, Cumberland County has seen history unfold outside and inside its brick walls. Now home to Pheasant Field Bed and Breakfast, the property dates back to the 1750s, before our nation's founding.

The former owners enslaved people until the mid-1830s, when a new family bought the land and freed them. Farm records and verbal tradition show they soon went a step further.

"As we moved into the Civil War, the Charles Hoffer family, who did not believe in slavery, offered this house as one of the sanctuaries for runaway slaves heading north," said Robin Stauffer, co-owner of Pheasant Field Bed and Breakfast.

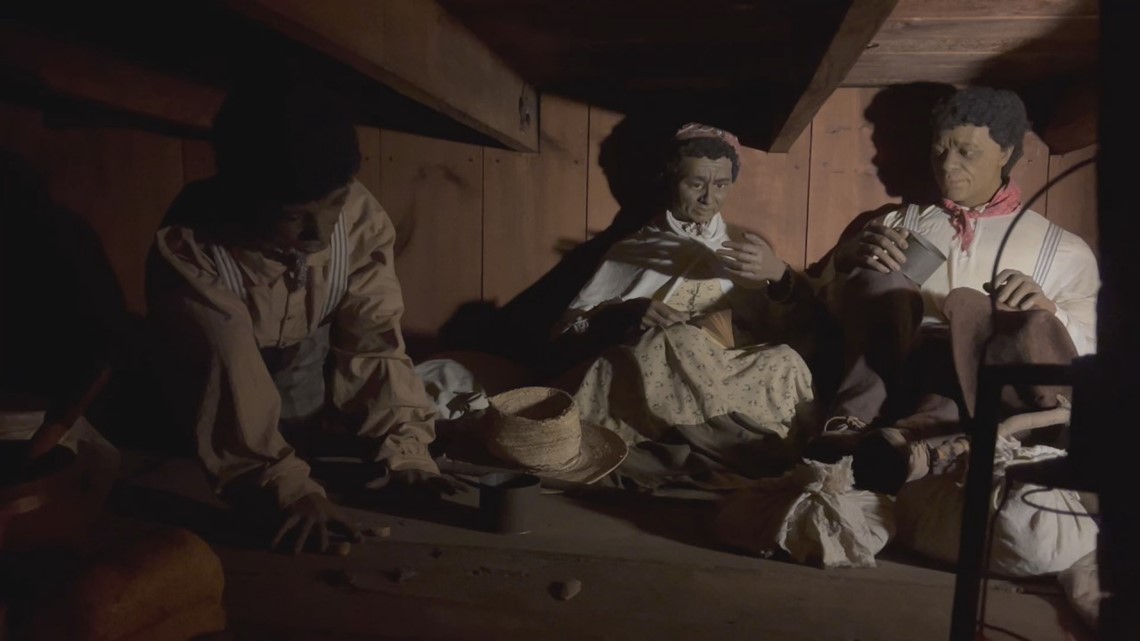

A standalone summer kitchen in the 1800s, one room would offer safety to an unknown number of people hoping to escape bondage.

"This cottage has a space in the floorboards that the slaves would come in and spend probably the daylight hours, because they moved primarily at night," Stauffer said. "This space here, the slaves would go down and hide in there."

"It's very small and confined," added Kathleen Stauffer. "If you really try to put your mind in the place of someone who's hiding down there, it's really intimidating."

It was intimidating and dangerous for the people seeking freedom, especially in Cumberland County, the last county in the state to end slavery.

"Most of the freedom seekers coming into our area are going to be coming from the Western Maryland and Eastern Virginia areas," said Matthew March, education director at the Cumberland County Historical Society.

They often traveled hundreds of miles, on their way to support in New York and Philadelphia or emancipation in Canada. Walking in the cover of night, they had to be careful about who was watching.

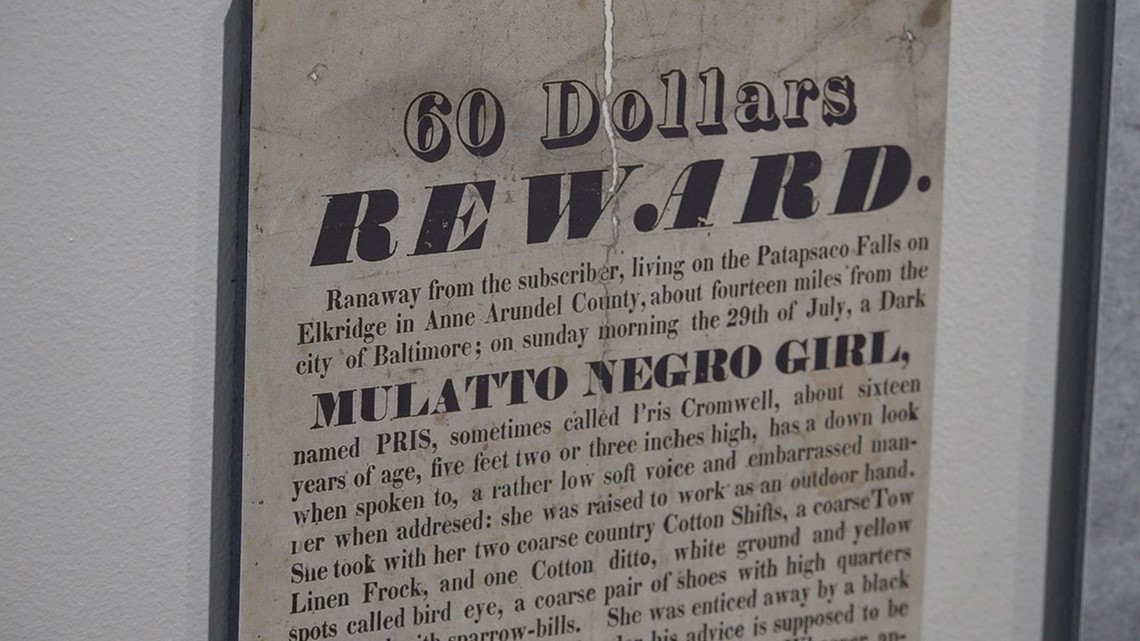

Slave owners paid big money to anyone who returned freedom seekers to the forced labor farms of the south. One posting, now on display in the Cumberland County Historical Society, offered a $60 reward, near $2,000 dollars in today's terms, for the return of a 16-year-old girl.

"The attitude wouldn't have been very pro-emancipation here," March said. "That's what makes the people who were willing to help, very remarkable."

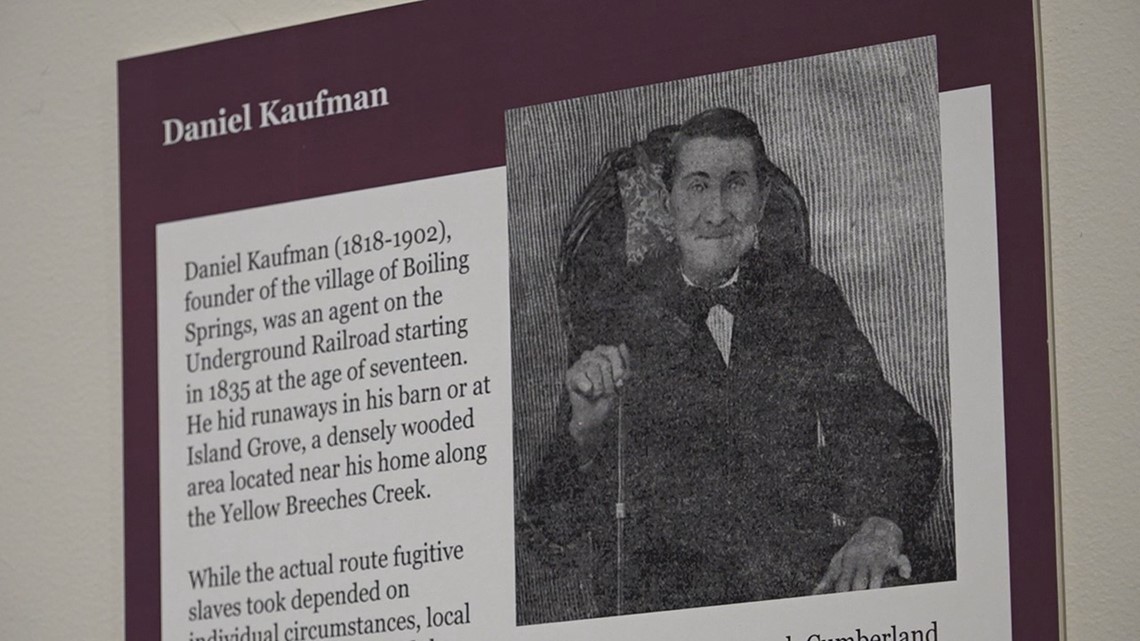

A few paid dearly for helping. In 1833, Daniel Kauffman began harboring freedom seekers on his farm outside of modern-day Boiling Springs at the age of 17.

"He had a little stone shack way on the edge of his property in a forest," March said. "They would've had shelter and water and really been far away from his house."

In 1847, 13 freedom seekers were found in Kauffman's barn. He'd be charged in Cumberland County for going against the Fugitive Slave Act.

Kauffman was later found guilty in federal court and forced to pay nearly $5,000 in fines. His actions were heard nationally, fueling the tensions that soon lead to the Civil War.

Long before the war's bloodiest battle, the town which would become synonymous with that conflict, helping people to freedom.

In 1776, Reverend Alexander Dobbin built one of the first homes in the Marsh Creek Settlement, modern-day Gettysburg. While historical accounts maintain Reverend Dobbin was an abolitionist, it's his son Matthew who acted.

"Matthew also was an abolitionist and the room that we're in right now was Mrs. Dobbin's kitchen," said Jacqueline White, owner of The Dobbin House Restaurant. "It was a one-story little room that connected to the house and Matthew added an addition."

While building on a second story around 1809, Matthew left a three-foot crawl space between the floors.

There, hidden behind a cupboard and roll-away shelves, verbal tradition holds Matthew housed people fleeing slavery.

"They would then be here during the day, hiding from bounty hunters," White said. "Then, at night, he would take them out and give them directions to the next station, they called it, on the Underground Railroad. The next safe house."

Matthew acted as a stationmaster until he moved west in 1825. While the scourge of slavery won't be ignored or forgotten, many freedom seekers found hope in South Central Pennsylvania.

"It's good to know that we're part of a house that tried to help these folks," White said.