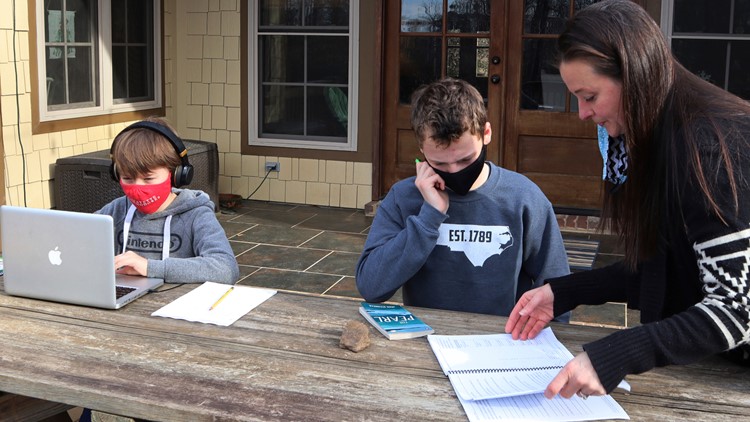

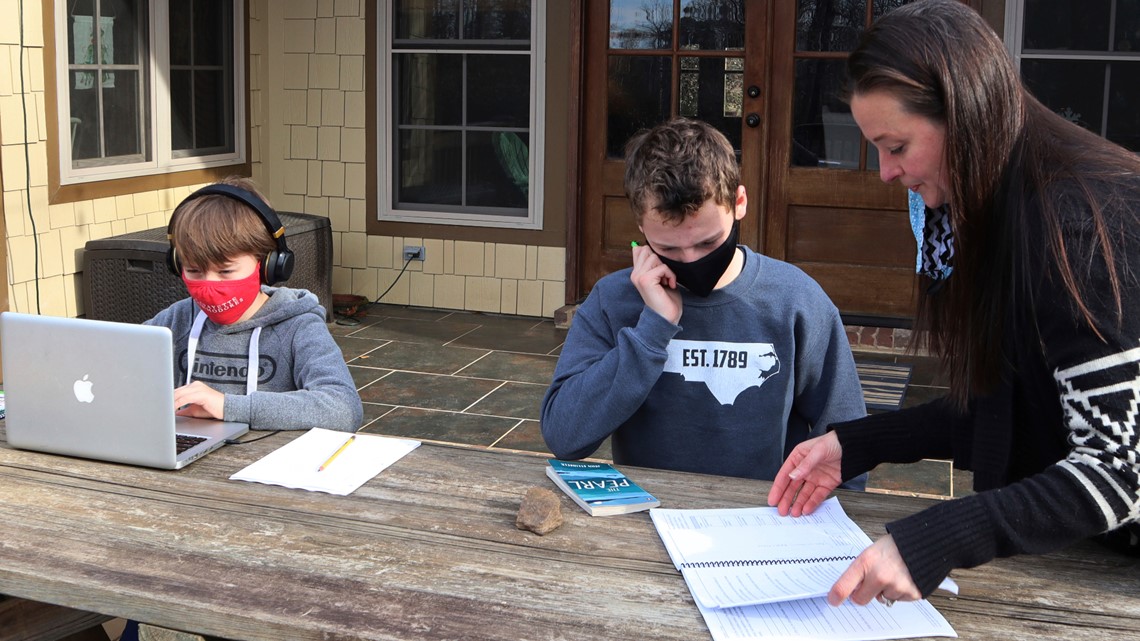

Fearful of sending her two children back to school as the coronavirus pandemic raged in Mississippi, Angela Atkins decided to give virtual learning a chance this fall.

Almost immediately, it was a struggle. Their district in Lafayette County didn’t offer live instruction to remote learners, and Atkins’ fourth grader became frustrated with doing worksheets all day and missed interacting with teachers and peers. Her seventh grader didn’t receive the extra support he did at school through his special education plan — and started getting failing grades.

After nine weeks, Atkins switched to home schooling.

“It got to the point where it felt like there was no other choice to make,” she said. “I was worried for my kids’ mental health.”

By taking her children off the public school rolls, Atkins joined an exodus that one state schools chief has warned could become a national crisis. An analysis of data from 33 states obtained by Chalkbeat and The Associated Press shows that public K-12 enrollment this fall has dropped across those states by more than 500,000 students, or 2%, since the same time last year.

That is a significant shift considering that enrollment overall in those states has typically gone up by around half a percent in recent years. And the decline is only likely to become more pronounced, as several large states have yet to release information. Chalkbeat and AP surveyed all 50 states, but 17 have not released comparable enrollment numbers yet.

The data, which in many states is preliminary, offers the clearest picture yet of the pandemic’s devastating toll on public school enrollment — a decline that could eventually have dire consequences for school budgets that are based on headcounts. But even more alarming, educators say, is that some of the students who left may not be in school at all.

“I would like to hope that many of them are from homes where their parents have taken responsibility on their own to provide for their education,” said Pedro Noguera, the dean of the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education, adding that affluent families will have an easier time doing that. “My fear is that large numbers have simply gotten discouraged and given up.”

So far, many states have held off on making school budget cuts in the face of enrollment declines. But if enrollment doesn't rise, funding will be hit.

“We’ve been trying to scream from the hilltops for quite some time that this is happening,” Kirsten Baesler, North Dakota’s schools superintendent, said of the enrollment declines. “And it could be a national crisis if we don’t put some elbow grease into it.”

The declines are driven by a combination of factors brought on by the pandemic. Fewer parents enrolled their children in kindergarten, and some students left public schools for other learning environments. At the same time, students who are struggling to attend classes, as many are right now, may have been purged from public school rolls for missing many days in a row. That is a typical practice, though there is some more flexibility now.

The Chalkbeat/AP analysis shows that a drop in kindergarten enrollment accounts for 30% of the total reduction across the 33 states — making it one of the biggest drivers of the nationwide decline. Kindergarten is not required in over half of states, and many parents have chosen to skip it.

Some aren’t sure it would be worth it for their children to learn virtually, while others don’t want their kids’ first experience with school to include wearing a mask.

It’s difficult to say how much of the decline is due to students leaving public schools for private schools and home schooling — as parents sought learning environments that might adapt better to the unusual year — because not all states track that. In states that do, those are contributing factors but don’t account for the full decline.

Massachusetts, for example, saw its K-12 enrollment fall by 3%, or nearly 28,000. Almost half of that was attributable to a big jump in students being home-schooled or switching to private schools, but about 7,000 students still are unaccounted for, state officials said. The year before, the state’s enrollment declined by less than half a percent.

Kira Freytag’s first grader, Landon, was among the Massachusetts students who transferred into a private school this fall. He was enrolled in public kindergarten in Newton this spring, but struggled with remote learning. When it looked like that virtual setup would continue, Freytag and her husband applied to a Catholic school with in-person instruction.

“There’s a lot of independence that comes with those years,” Freytag said. “It’s really hard to teach that over Zoom.”

Some states have gone to great lengths to try to figure out where students are. When the schools superintendent in Mississippi, Carey Wright, saw that K-12 enrollment had plummeted by 4.8%, or nearly 22,000 students, she asked officials to track down every student who’d been enrolled the previous year. They mailed letters, placed calls and even made home visits.

They found that kindergarten enrollment fell by 4,400 students and 6,700 more students enrolled in home schooling than usual — an increase of 36%. More students than usual also moved out of state. And some 2,300 students transferred to private school. That left the state with around 1,100 students it could not account for, though it’s still trying.

“We could not afford to have kids just at home, doing nothing,” Wright said.

Many states haven’t been able to track down all the students who left. Some students may be getting home-schooled, but their state doesn’t require families to register them. Some may have moved across state lines and haven’t transferred their records. Others may have stopped attending school because they are experiencing homelessness, lack a stable internet connection, are working to support their families or are caring for siblings — and then were dropped from their district’s rolls.

Renee Smith, who helps low-income families navigate school options through her work at the parent advocacy group Memphis Lift, said some families in her city have turned to Khan Academy, a source of free online lessons, as an alternative to the local district’s virtual learning option, but others “have just disappeared.”

One open question is whether students who exited the public school system will return when instruction gets closer to normal. Many educators believe young learners who sat out kindergarten will return, but they’re worried about older students.

And many state superintendents and education advocates say there needs to be more done by school districts, state officials, and social service agencies to find the missing students.

“The things which make the difference are not cheap,” said the Rev. Larry Simmons, who’s involved in an effort to reduce chronic absenteeism in Detroit. “Human beings reaching out to other human beings, saying: ‘We miss you, we want you at school.’”