PENNSYLVANIA, USA — A Canadian university has quietly made public Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano's 2013 doctoral thesis about a legendary World War I hero, including six pages of recently added corrections that, in some cases, do not appear to fix anything.

Researchers who have long criticized Mastriano's investigation into U.S. Army Sgt. Alvin C. York as plagued by factual errors, amateurish archaeology and sloppy writing say the dissertation, released last month by the University of New Brunswick, echoes the problems in his 2014 book based on the same research.

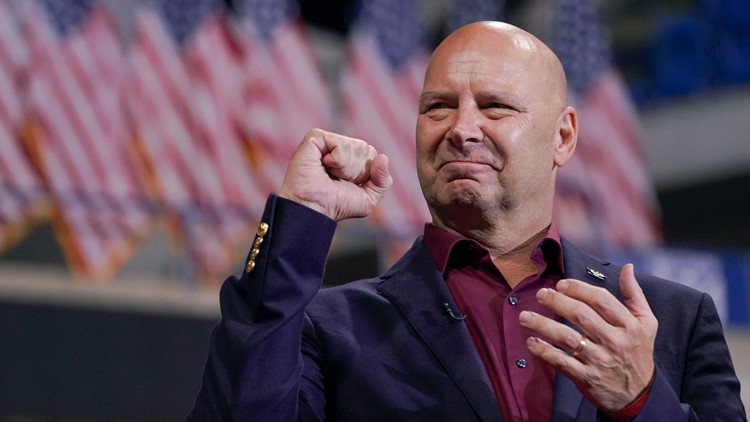

Mastriano won the Republican primary in May thanks, in part, to a late endorsement by former President Donald Trump. He came to political prominence by leading protests against pandemic mitigation efforts, energetically supporting the movement to overturn Trump’s 2020 reelection defeat and appearing outside the U.S. Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection.

The far-right state senator, a retired Army colonel, regularly brings up his Ph.D. status in public remarks and on the campaign trail as evidence of his knowledgeability. When a photo of Mastriano wearing a Confederate uniform surfaced last month, he brandished his academic credentials as a defense of his credibility.

Mastriano’s 480-page thesis includes a retelling of York’s life story and the results of Mastriano’s own research. The version now online has Mastriano’s June 2021 corrections, appended after a complaint from another researcher prompted the university to review the work.

A University of New Brunswick history professor, Jeff Brown, provided documents to The Associated Press that recorded his own misgivings about the dissertation nearly a decade ago when he was on Mastriano's doctoral committee. He says he was “appalled” by the dissertation and “disturbed by the fact that no one on the committee was qualified to evaluate the huge part of it that was archaeological.”

Brown said he flagged glaring issues to other faculty members and administrators and was dismissed from Mastriano's committee by the lead adviser — yet the published dissertation still listed Brown on the title page, giving the impression that he endorsed the material.

Brown said in an email that Mastriano’s main adviser, now-retired history professor Marc Milner, told him “that as it turns out, I never really needed to be on the examining committee after all, so there was no need to worry about evaluating Mastriano’s dissertation (despite the fact that I had already done so).”

“This was presented to me as a favour, to relieve me of the necessity of having to decide whether to sign off on it or not,” Brown added. “I never understood how I suddenly became superfluous.”

Neither Milner nor Mastriano responded to multiple requests for comment.

The 21 revisions made last year, numbered in a list that skips from No. 9 to No. 11, include altered footnote references along with several changes that do not actually appear to correct anything but instead add descriptive text or defend aspects of the dissertation.

The most significant correction involves his longstanding claim that a photo of an American soldier leading German prisoners was misdated and mislabeled by the military photographer in 1918, and that it in fact shows York with three officers he would force to surrender two weeks after the date.

Mastriano's certainty about the American soldier's identity has evolved over the years: He wrote in 2007 that the photo “is now believed to show” York, then was “fairly sure” in 2011, described York as “clearly identified” in the 2013 dissertation and declared in the 2014 book that the photo “is confirmed to be" York. But his new explanatory footnote backtracks, saying it “seems to show Corporal York marching his prisoners into the American lines, with what is likely the German officers.”

“He didn’t ‘fix’ that — he just doubled down on his ridiculous assessment,” said University of Oklahoma history graduate student and instructor James Gregory, the complainant who triggered New Brunswick's review.

He said Mastriano’s revisions ignored more than a dozen of the problems Gregory found in the book and argued Mastriano “has no evidence other than this guy has a mustache and looks like Alvin York.” Gregory is preparing a similar list for the Canadian university with what he has identified as the dissertation’s errors.

A spokesperson for the University of New Brunswick, Heather Campbell, said Mastriano's “credentials are not impacted” as a result of the corrections and the school’s review. And retired history professor Steve Turner, another committee member, wrote in an email last week he stands by the decision to accept Mastriano’s thesis and grant him a doctorate.

“There was no reason to question the authenticity or accuracy of the sources cited in footnotes,” Turner said.

Turner said he did not recall that Brown raised concerns about the work but remembered Mastriano as “respectful and polite” during a meeting in which Turner urged him to engage more directly with critics of his research.

“I believe the truth is nonexistent in Mastriano’s vocabulary, but the word ‘detractors’ is and he applies it to anyone who is in disagreement with him,” said one of those critics, British author Michael Kelly. Kelly's 2018 book, “Hero on the Western Front,” includes a section on the controversy over Mastriano’s findings.

Mastriano claims to have pinpointed where York engaged in the gun battle with German troops for which he received the Medal of Honor. But critics like Kelly call his work shoddy and substandard, built on falsified evidence and bald assertions.

Penn State history professor Dan Letwin, asked to evaluate the dissertation’s quality, said it does not appear to meet current academic standards for doctoral-level historical research, describing it as “very lacking.”

“There’s nothing interpretive here about big historical questions,” Letwin said.

Last year, after Mastriano's book was questioned, New Brunswick officials declined to comment on the dissertation without Mastriano's permission.

But earlier this summer, the dean of New Brunswick’s school of graduate studies, Drew Rendall, came back from a yearlong sabbatical to learn Mastriano's dissertation was still under embargo. Embargoes of a few years are not uncommon in academia, particularly when there are plans to turn the work into a book, but it's unclear why the embargo on Mastriano's dissertation more than doubled the school's usual four-year limit.

Rendall said he notified Mastriano the thesis was being made public but never received a reply.

The 2014 book 's publisher, the University Press of Kentucky, is also planning corrections if it does another printing. Mastriano was sent a list of about 30 questions, some regarding minor typos and others seeking “additional sources to confirm specific information in the book,” press director Ashley Runyon said in an email.

The publisher plans to use his responses and its own review of primary sources “for future printings of the book to correct any errors,” Runyon wrote. Mastriano was informed of the proposed changes but has not responded, and the press has the final say in the revisions, Runyon added.

The book, which features the photo of a soldier leading German prisoners inside and on its dust jacket, is going to be changed to add information about the dispute in a preface, she said.