Willie O’Ree first crossed paths with Jackie Robinson in 1949, two years after the Dodgers legend broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. O’Ree was 14 years old, well ahead of making history himself.

Before he became the first black player in the National Hockey League, and even longer before he was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame, O’Ree was visiting New York. Back then, he was playing two sports. His baseball team had won a championship, and the reward was a trip to see the Empire State Building and Radio Music City Hall.

“I met Mr. Robinson after a game,” O’Ree, now 83, told CNN Sport’s Patrick Snell. “I shook hands with him down by the dugout. And (I) told Mr. Robinson that I not only played baseball but I played hockey, and he remarked that he didn’t know that there were any black kids playing hockey.”

The two would meet again in 1962. By then, it had been four years since O’Ree had broken the NHL color barrier. He was no longer in the league, but he had continued to play in the minors. O’Ree was in Los Angeles, playing for the Blades of the Western Hockey League.

The NAACP had a luncheon for Robinson in the city, and O’Ree received an invitation with his coach and two other players through the hockey club.

After speaking with the media, Robinson was introduced to the players.

“Mr. Robinson turned around and looked me in the eye and pointed and said, ‘Aren’t you the young fella I met in Brooklyn?'” O’Ree recalled. “He remembered me from meeting in 1949.”

On Monday, O’Ree will be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto. He was elected in the builder category for his contributions to the game, and his induction comes 60 years after breaking the color barrier.

“I am very grateful and very honored to be selected to go into the Hall,” he said. “It is one of the highest awards in hockey, and I never dreamt of being in the Hall.

“But thanks to the work that I am doing now and a lot of the influence of people that wanted me to have the opportunity to get in made it possible for me.”

Playing with one eye

O’Ree was born October 15, 1935, in Fredericton, New Brunswick in Canada. He started skating at three years old, and he began playing organized hockey aged five. It was when he was 14 that O’Ree, a winger, decided he wanted to pursue playing in the NHL.

But becoming a pioneer in the sport almost didn’t happen. While playing at the junior level for the Ontario Hockey Association’s Kitchener Canucks in the 1955-1956 season, O’Ree took a puck to the face and was hospitalized for three days.

“None of the players back then wore any headgear, no facial gear, and I was in front of the net,” O’Ree said. “There was a slapshot. The puck came up and struck me in the right eye.”

O’Ree said he lost 97% of his vision in that eye, and the doctor told him that he would never play hockey again. It was a medical opinion that O’Ree did not accept.

“He didn’t know the feeling that I felt inside,” O’Ree said. “When I got out of the hospital and found out that I could still see, I just told myself that I still have one eye and I was still going to pursue my dream.”

Learned he made history by reading the newspaper

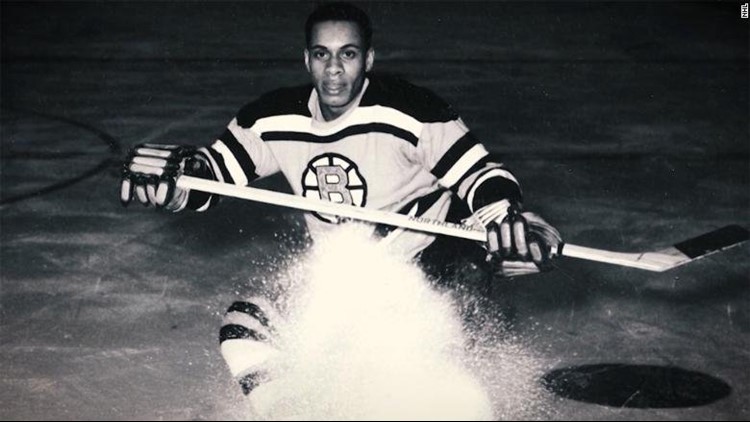

In 1958, while O’Ree was playing for the Quebec Aces in the Quebec Hockey League, he received word that the Boston Bruins — one of just six teams in the league at the time — wanted to add him to their roster to replace an injured player for two games against the Montreal Canadiens.

“When I arrived in Montreal, I met the coach, Milt Schmidt, and the general manager, Lynn Patrick,” O’Ree said. “They sat me down and said, ‘Willie, we brought you up because we think you are going to add a little something to the team.'”

O’Ree was no stranger to the Montreal fans because he had played against the Canadiens in exhibition games. “But, this was a regular scheduled NHL game,” he said. He had butterflies that day, which was January 18, but they didn’t last.

“Once they dropped the puck and I got involved in the first shift, I just settled down and played my game,” O’Ree said. “We were very fortunate to beat the Canadiens that night. We shut them out 3-0, so that was another treat for me.”

While he understood the significance for himself of fulfilling a career goal, he didn’t realize in that moment by stepping on the ice, he had become the first black player in NHL history.

“I didn’t realize that I was breaking the color barrier until I read it in the paper the next morning,” he admitted.

The Jackie Robinson of hockey

There was something O’Ree did in his early days that Robinson didn’t do in baseball. In his sport, he fought.

“I had to fight because I had to protect myself and basically just let these players know that I have the skills and the ability to play in the league at that time,” O’Ree said. “I wasn’t going to leave the league because players on the opposition were trying to get me out of the game.”

He said that in every game he played in, he heard name calling from opposing players and from fans in the stands. He said he “let it in one ear and out the other” and concentrated on just playing hockey.

“Besides being black and being blind in my right eye, I was faced with four other things: racism, prejudice, bigotry and ignorance,” O’Ree said.

In all, O’Ree’s career in the NHL was brief. In his two stints with Boston, first in 1958 and in the 1960-1961 season, he played in 45 games, scored four goals and had 10 assists. But he stayed in hockey much longer than that. The journeyman minor leaguer retired from the sport in 1979 at age 43.

O’Ree has spent the past 20 years as an NHL ambassador. In 2008, he received the Order of Canada for his work growing the game around the world. And now, he’s a hall of famer.

When he was recalled by the Bruins on November 18, 1960, the media dubbed O’Ree as “the Jackie Robinson of hockey.” And while his story isn’t as well known as Robinson’s, O’Ree has left an indelible mark in the sport.

“I’m honored and very grateful that I am even in the same category as Mr. Robinson,” O’Ree said.