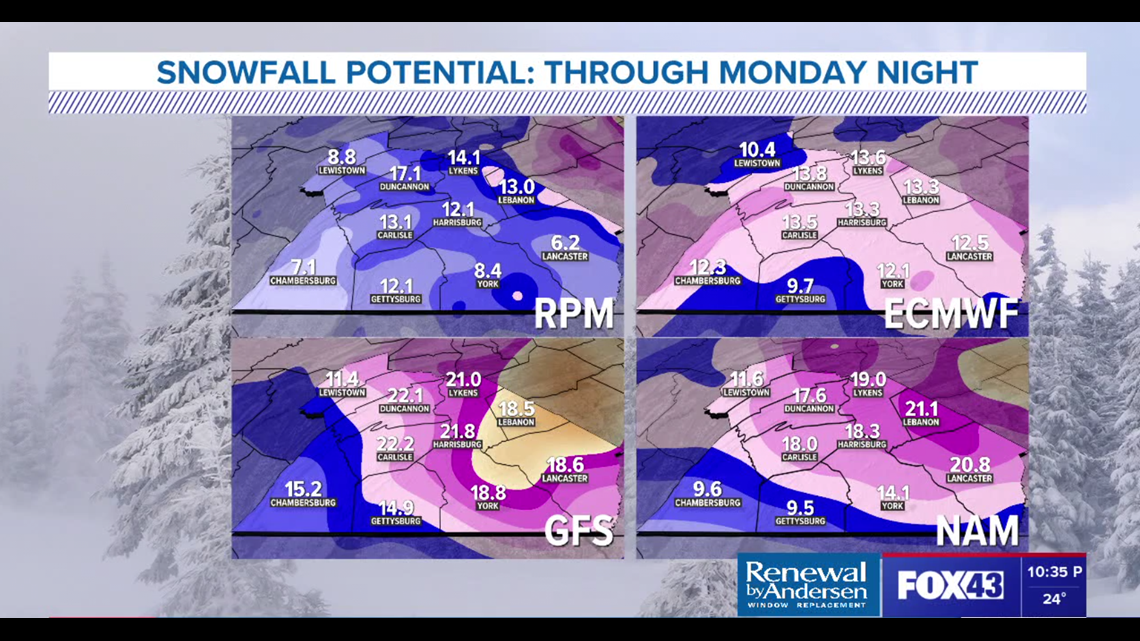

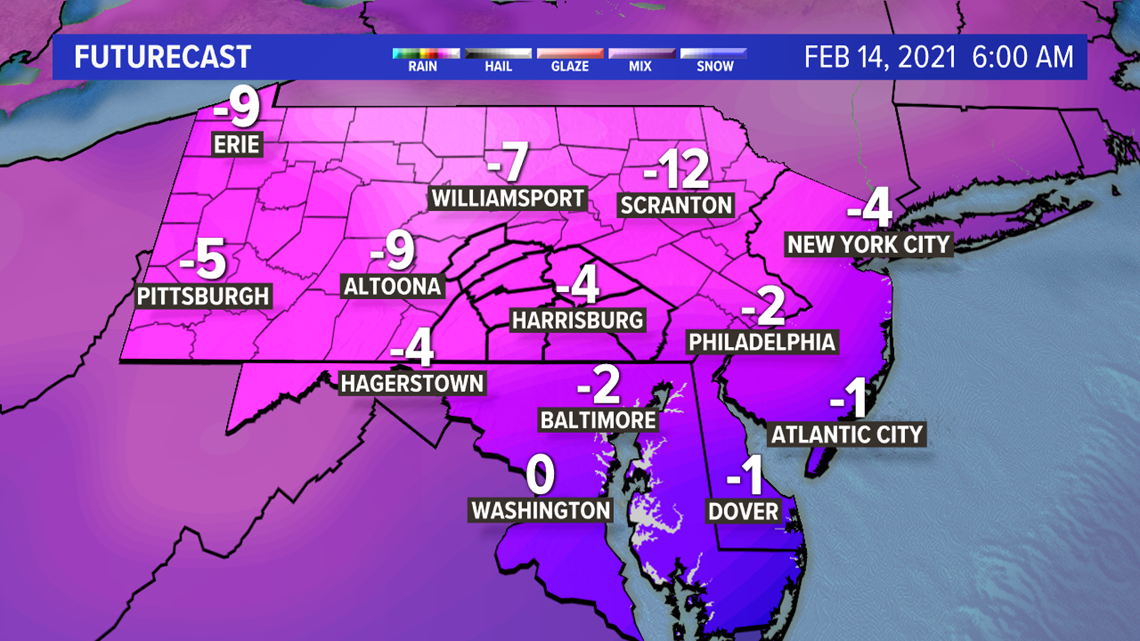

PENNSYLVANIA, USA — “These totals can change, so stay tuned for updates.”

Yet another famous line from yours truly. It’s because there’s no Magic 8-Ball in forecasting, no rodent-inspired holiday, and no one particular weather forecasting model that can tell you exactly what’s going to happen.

That’s because each model is designed differently, and each one handles elements of a forecast in a variety of ways. It’s our job to know these biases and adjust our forecast accordingly.

And by the way, sometimes these biases adjust from year-to-year, or season-to-season.

Here’s the problem: our forecast adjustments to these model biases also are not fortune tellers. In fact, most models we look to predict the weather are ensembles—meaning they are a compilation of OTHER models. Models on models on models. One may emphasize temperature. Another may emphasize wind speed. Another may think that it’ll rain more. Dozens of them. Not one will get it exactly right. And then, those “ensemble members” are crammed together and blended to make one big model of what it believes is most likely to happen.

And then we look at OTHER models exactly like this! It’s quite literally insane. I’m saying it. All meteorologists are insane if they love what they do in this inexact science.

This is a very oversimplified, dumbed-down version of what we go through each and every day to make the forecast. Meteorologists with a doctorate will read this and cringe at how I've simplified all this to help us understand what goes on here. But, that’s why this is a blog, and not a peer-reviewed paper. (That’s also why I have a Bachelor’s, and they have a DOCTORATE.)

Moving on! For us here in North America, we generally rely on a handful of models for everyday life and then delve deeper into others for a winter storm, a hurricane or a severe weather setup.

Some of these include:

NAM (North American Mesoscale) comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. It’s a shorter-range model that we generally use for the next 2-3 days. It is one of the primary models run by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP). That’s a whole other blog.

Anyway, this year when I forecast, I automatically throw out the temperature. It runs cold, sometimes by several degrees. I may literally not even bother to write it down. However, it’s short-range precipitation tends to be pretty good, and sometimes its temperature in the higher levels of the atmosphere line up pretty well.

GFS (Global Forecast System) is another NCEP-produced model that puts out dozens of forecast elements like temperature, winds, precipitation, soil moisture and more. It’s not perfect. It tends to overdo precipitation this year and amplifies severity in general. However, it had a win this past week in our snowstorm as it passed over Chicago before hitting us. It covers the entire globe and predicts weather 16 days out. Do we look at it 16 days out (hour 384)? No. Do you see “media-rologists” on social media who think they know what they’re talking about post this 16-day forecast? You bet. And it’s always (pejoratively speaking) wrong. The number of three feet snow storms or 50-degree temperature swings I see on models that far out reign back in each and every single time.

Why? It’s the butterfly effect of meteorology. If a 5MPH predicted wind by the GFS at hour 216 is actually a 10MPH wind, then the temperature in Cambodia could be 3-degrees higher which then prevents the intensification of a tropical storm off the coast of Africa two days later and therefore a category 5 hurricane is avoided. Not literally, but you get the idea. The further out the model, the more variables, the more inaccuracy.

ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast) – woof, that’s a name. It’s run by an independent intergovernmental entity supported by 34 European nations. And, as opposed to the NAM and GFS, which are ran by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and are free, the Europeans can, and do, charge for their data – though some is free to the public and that is what we use in our forecast.

As a result, I can’t tell you a whole lot about how the ECMWF is designed, but I can tell you that it’s usually our favorite. It’s made up of 51 ensembles and one global model with a similar suite of tools to the GFS. Overall, we just notice fewer “busts” in the forecast with the ECMWF and it really handles precipitation, usually, better. This likely proves true because of a variety of non-scientific factors like bureaucracy, funding and more.

At the risk of boring those of you who have made it this far even more to death, here’s a list of other, models we look at, some on a regular basis and others not so much. Luckily, you can just click on these links for more information on them.

- HRRR (High-Resolution Rapid Refresh)

- CFS (Climate Forecast System)

- GEFS (Global Ensemble Forecast System)

- SREF (Short Range Ensemble Forecast)

- GEM (Global Environmental Multiscale Model)

Trust me, this is not all of them. Not even close.

To wrap up, while I generally am giving you a rundown of a few models we look at, why and what they do, I hope you come to understand a few things here.

- Stop sharing particular runs (because these models, by the way, are carried out multiple times a day) of snow totals, hurricanes, even temperatures days out. You’re wrong.

- Don’t expect us to give snowfall totals days in advance. We will 36 hours out. There’s a reason (see entire weather blog above).

- And, most importantly… stop the age-old phrase “It must be nice to be wrong half of the time and keep your job!”

Our job is one of the most complicated jobs in the world. If we were wrong the night before about what you’re seeing today, we were probably off by two degrees, or two inches or two extra clouds in the sky. Forecasts like snowstorms we had this past week are immensely complicated (and by the way, we pretty much nailed this last storm on the head, start to finish – just saying). We definitely adjust our seven-day forecast at the end a decent amount. By day three, we’re closing in. We always do our best, care about you and how weather affects your life. We have thousands of variables at play for the sunniest, nicest of days.

In the words of President Biden, “C’mon, give me a break, man.”

Until next time,

-Chief Meteorologist Bradon Long