YORK, Pa. — With Spring in full bloom (pun intended) across the commonwealth, soils are thawing as growing season begins.

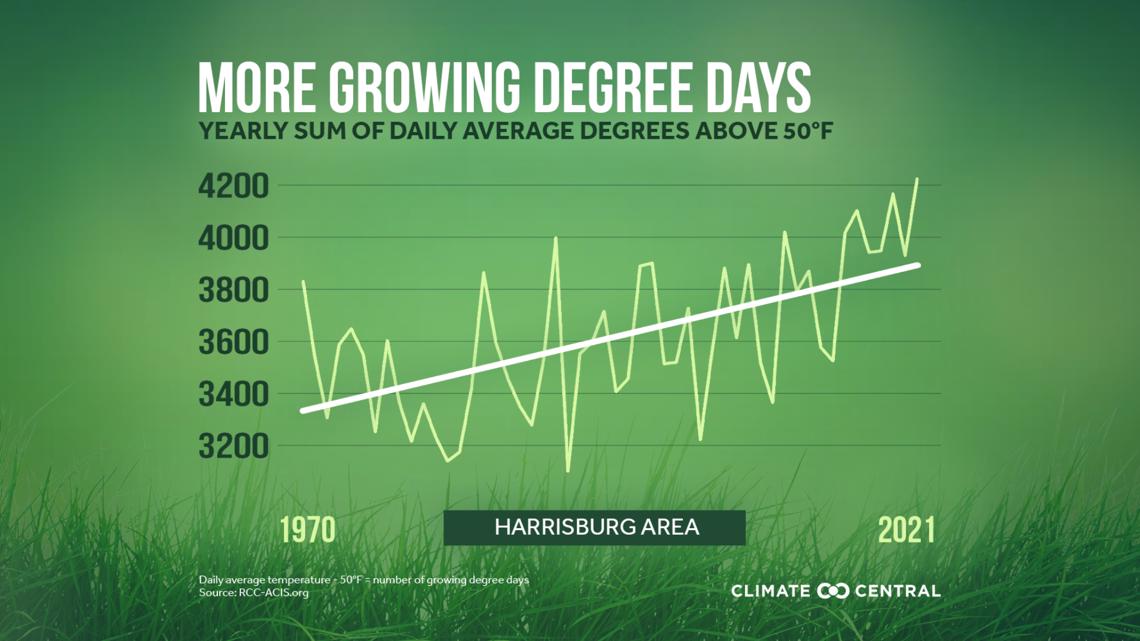

But since 1970, the number of growing degree days has also grown as our climate warms.

Think of a growing degree day as a measure of heat accumulation. It's the amount of heat necessary for a plant to go from one stage of growth to another. They have to accumulate a certain amount of heat to go from one stage to the next. And this can be a lengthy process.

"Every plant has a growth stage," says Dr. Suat Irmak, head of biological and agricultural engineering at Penn State University. "There can be from 10 to 12 to 14 different growth stages. Corn has 16-18.

"To go from planting to emergence, plants have to accumulate X-number of growing degree days."

These growing degree days are accumulated by above average temperature. For example, tomatoes have a base temperature need of 50°F.

A day with an average temperature of 60°F would equal ten growing degree days (GDD).

Irmak said in a normal year, plants have to accumulate a minimum of around 2,000 GDD. Corn reaches maturity around 3,000 GDD, according to Climate Central. This is typically done in five months or so, between May and early October.

"If the climate gets warmer, and they accumulate growing degree days at a faster rate, they're going to accumulate that not in five months, but in four months," Irmak said. "This has huge implications."

Irmak said that many people might argue this is good. A shorter growth time could mean farmers might be able to squeeze in another crop.

"That is technically correct, but that is going to bring up other issues," Irmak said.

Increased pests, crop disease and general over-working of the soil are all concerns if farmers choose to go this route. And that's if the crops survive with increased heat accumulation.

More growing degree days obviously means more heat. Warmer growth conditions cause more evaporation, meaning that plants can't hold onto moisture critical for growth.

Now, here you may think: "Bradon, I've read your blog before. You said warmer temperatures can increase precipitation. What gives?"

Yes, that's true.

We're coming off some of the wettest years on record in Pennsylvania. But, as farmers will tell you, too much rain also can devastate crops and ruin soil beds. And increased temperature won't distribute the precipitation evenly. Wet areas will get more wet, dry areas will get more dry.

That would leave drought-prone areas like where I'm from, in Northwest Oklahoma, more prone to increased drought, wildfire and crop loss as well.

On top of those threats, increased temperature and a faster growth rate mean less yield, according to Dr. Irmak.

"If you increase your temperature, this isn't only occurring at daytime," Irmak said. "Nighttime temperatures have respiration implication."

Essentially, without cooling enough, crops can't process their metabolic activities as efficiently, reducing yield.

Still, it's not all doom and gloom. Irmak has spent more than 20 years with farmers all across the country, one-on-one. Technology and the farmers themselves give him hope for the future.

"We have to work with our producers, who are doing the hard work by the way. They are the best stewards of their lands. They care about their lands more than anybody," Irmak said. "If they're not exposed to those new technologies and implement in their production fields, we may not be able to mitigate against anything."

Technologies including carbon-cutting systems, reduced and no-till processes, drought tolerant selection and proper row spacing to reduce evaporation loss are all actions taking place reducing climate change's impact on crop development as a whole.

And as Irmak also noted, agriculture has been the backbone of civilization for millennia. It's not going away. Mouths to feed, jobs to do, fuel to produce, agriculture impacts every part of our lives.

"I'm not giving up on anything," Dr. Irmak said. "There is no other way."

Until next time,

-Chief Meteorologist Bradon Long