Odds are, you at least heard that the United Nation's International Panel on Climate Change issued a "code red" report for climate change earlier this week.

While it's true that scientists have been warning about the climate for decades, and yes, former vice president Al Gore being a big spokesperson perhaps made you think it was a politicized issue - but it really is almost too late if you're not already paying attention.

There is a lot to digest in this report, the first of it's kind since 2013. The report has more than 200 authors detailing 14,000 studies. It's nearly 4,000 pages long. The more basic version is still 42 pages long.

But, the first major bullet point in the report couldn't be more clear.

"It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred."

Not that things WILL occur -- they HAVE occurred.

According to the report, observed increases in well-mixed greenhouse gas concentrations since the 1750s are caused by human activities. This includes carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide as the primary contributors. (You'll remember my story on the Carbon Skyscraper to understand the rate of increase of carbon dioxide and its dangers.

RELATED: How 800,000-year-old Antarctic ice turned into a clear case for climate change | Climate Smart

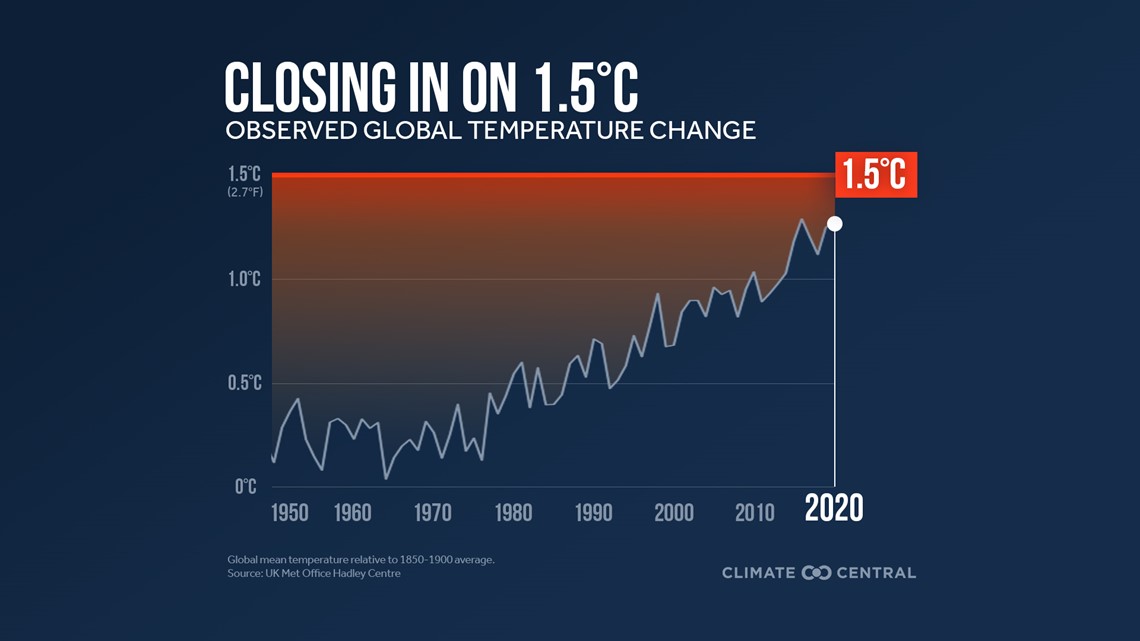

Each of the last four decades have been successively warmer than any other decade before it since 1850.

But perhaps the most single important fact in this report -- at the center of it all --involves global surface temperature. It has increased by 1.09°C since 1850 (near 2°F). That's the number that everyone will talk about.

Why? We're rapidly approaching a number we don't want to cross: 1.5°C.

That's the benchmark scientists and politicians alike have set for us to not cross in the Paris Climate Agreement. The impacts beyond 1.5°C, while not yet fully comprehended, dwarf what effects we've already seen in the past decade. It's also a high increase from a 2018 study for the years between 2006-2015, which set the increase at 0.87°C.

Here's some of what the report says we have seen.

1. Global average precipitation over land has increased.

The report details not only an increase in precipitation, but that storm tracks are trending further and further poleward in the mid-latitudes. This means that in the northern hemisphere, large precipitation events are occurring further north, and the opposite in the south. This is because, as the temperature warms, the ideal temperature for these sorts of events shifts towards the poles.

You may also ask, "how has precipitation increased when we keep talking about wildfires?"

That leads us to the next point.

2. Changes in climate increase frequency and strength of extreme weather.

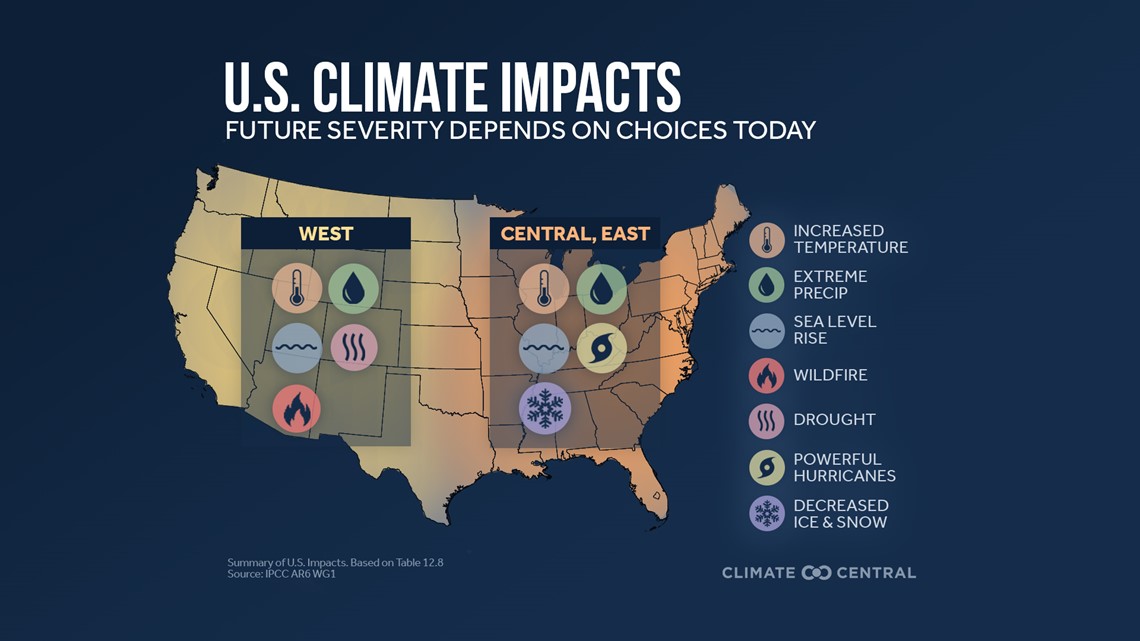

Here's how: Each different climate zone has a different amount of moisture within it. Take the U.S. for example -- our western states are drier than our southern states. For it to rain, the air has to be saturated -- the dew point and actual temperature have to nearly match.

In the west, that means you need more moisture. But if the temperature increases, you're only forwarding the divide in temperature and dew point, not bringing it closer. Whereas in the south, you're creating a more unstable environment for the moisture that's already there to sustain thunderstorms. So, warming temperatures increase potential precipitation in already wet areas, whereas they worsen drought and heat waves in traditionally dry areas.

General climate zones (i.e. tropics, mid-latitudes, tundra) are shifting poleward as well -- in coordination with the aforementioned storm track.

Extreme heat is occurring more often and stronger. The frequency of heavy precipitation events in already moist areas is increasing. The proportion of major (Category 3-5) hurricanes has increased in the last four decades. All likely due to not just warming, but a human influence.

3. Our glaciers are still retreating.

Human influence is "very likely" the main driver of the global retreat in glaciers since the 1990s. In 2011-2020, annual average Arctic sea ice reached its lowest level since 1850, with almost all of the world's glaciers retreating at the same time. This has driven the start of sea level rise, which has increased by 0.2 meters (7.87 inches) since 1901.

That may not sound like much. However, higher sea levels means disruptive storm surges from tropical systems push further inland than they used to, causing more nuisance flooding. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says that disruptive and expensive flooding ranges from 300-900% more frequent within U.S. coastal communities than it was just 50 years ago.

Meanwhile, sea level has risen much more rapidly (by eight inches) in South Florida since 1981 - near a city much more susceptible to the slightest increase in sea level rise. NOAA released a report in 2017 detailing the danger to the coastal city, among others. Jeff Goodell, author of peer-reviewed The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities and the Remaking of the Civilized World, put Miami on his list of eight cities likely to disappear by 2100, as did the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

4. The upper levels of the ocean are becoming more acidic.

When carbon dioxide enters the ocean, it dissolves in the saltwater. As it breaks down, it forms bicarbonate ions and hydrogen ions. To keep it simple, the more hydrogen ions in the ocean, the more acidic. While ocean life relies on carbonate ions to survive, the more hydrogen ions you put in, acidity rises. Oxygen levels have dropped in many upper ocean (0-700m) areas since the mid-20th century as well.

There's obviously more to be read in the 3,949 page report. There's even more to be read in just the 42 page Summary for Policymakers. But, if I haven't lost you now, I will lose you there. So, you can visit the IPCC's website for more information.

But, the point to drive home is clear: the phrases virtually certain, very likely, likely and high confidence appear more often in the report, the sixth of its kind in history, than ever before. And more often than not, it's before the words "human-induced."

So, keep an open mind when reading the report. Check out the Climate Smart series for more information as well on how increasing carbon dioxide levels have impacted us here at home. Sit on it for awhile. But, not too long -- because the overwhelming majority of the scientific community says, we may not have that long to make important changes for the future.

Until next time,

-Chief Meteorologist Bradon Long